It’s a shock to walk into a branch of WalMart to be greeted by the sight of three security guards brandishing the kind of major weaponry currently being used elsewhere to pulverise Isis and their victims to pieces. It’s simultaneously comforting and disconcerting to see that no-one else is paying the slightest attention to their presence, in fact the three Robocop clones are acting just like security guards might elsewhere, except for the fact that they are dressed for World War Three, or possibly Four. I don’t ask. They are strolling around, yawning and playing disconsolately with their Motorolas, eying up the Pick n’ Mix and looking ready to blast into space anyone who looks like they might try to smuggle a 48-inch flatscreen down their trousers. I only popped into the place to buy a tiny bottle of Mezcal to entertain myself with post-work while watching the IT Crowd on Netflix; not finding one, I contemplate the possible consequences of trying to leave empty handed. For the first time in my life I am genuinely apprehensive that someone might shoot me dead unless I purchase some alcohol.

It’s a shock to walk into a branch of WalMart to be greeted by the sight of three security guards brandishing the kind of major weaponry currently being used elsewhere to pulverise Isis and their victims to pieces. It’s simultaneously comforting and disconcerting to see that no-one else is paying the slightest attention to their presence, in fact the three Robocop clones are acting just like security guards might elsewhere, except for the fact that they are dressed for World War Three, or possibly Four. I don’t ask. They are strolling around, yawning and playing disconsolately with their Motorolas, eying up the Pick n’ Mix and looking ready to blast into space anyone who looks like they might try to smuggle a 48-inch flatscreen down their trousers. I only popped into the place to buy a tiny bottle of Mezcal to entertain myself with post-work while watching the IT Crowd on Netflix; not finding one, I contemplate the possible consequences of trying to leave empty handed. For the first time in my life I am genuinely apprehensive that someone might shoot me dead unless I purchase some alcohol.

Security (or, rather ‘security’) is generally pretty visible these days in Boca del Rio. This seaside suburb of Veracruz was the site of an incident remarkable even by the standards of Mexico’s mid-level civil war, when, on 20 September 2011, 35 corpses were dumped in the street outside a shopping centre by one of the rival gangs of narcos said to dominate the state. The Governor of the State of Veracruz, Javier Duarte de Ochoa, called the episode ‘abhorrent’. Duarte is doing his best to control the situation as he knows best, taking regular lessons from his idol and role model General Franco. He is particularly keen to control the media, particularly when it takes photos of him looking overweight, and he also keeps a keen eye and a heavy fist on the activities of groups of students who try to challenge his rule and hold him accountable. He also keeps himself busy violently refuting persistent and seemingly well-founded allegations that he is directly connected to the activities of narco cartels in his state.

So whenever I come here (it’s my third visit) I find that the word regime tends to play on my mind, partly because in this state, unlike in Mexico City, the ubiquitous state police tend to wear military camouflage uniforms and drive around with heavy armoury mounted on the back of their jeeps. Still, largely because the role of the repressive apparatus is partly to keep the city safe for tourists and business travellers, it feels safe enough, indeed extremely pleasant, to walk around in the sunshine. As I stroll along the malecón I come across a monument to a century of Lebanese immigration, possibly paid for by the country’s most famous Lebanese descendant, who is also one of the world’s richest (and quite possibly dodgiest) men. A hundred metres further on a similar monument, unveiled by the country’s President in 2012, commemorates Jewish immigrants, presumably many of whom fled what Benjamin Netanhayu apparently regards as the Palestinian-inspired Holocaust. Certain kinds of visitors and migrants are therefore welcomed by the regime, others not — in a stark contrast with the two monuments, right across the street above a hair salon is the Honduran consulate. According to Amnesty International (the organisation under whose auspices I myself am ultimately here in the country), Mexico has become a “death trap for migrants”, with tens of thousands of people who are fleeing violence and poverty in Central America and trying to reach the US facing a serious risk of mistreatment, kidnapping and murder along their tortuous route at the hands of both state authorities and drug gangs (in Mexico these are very often the same people). It’s hard to correlate this with my own direct experiences, which are better reflected in a separate report by something called Expat Insider magazine, which places Mexico in second position in terms of its ‘expat quality of life’, with “nine out of ten expats describ(ing) the attitude of the Mexican people toward foreign residents to be friendly”. My instinctive abreaction to this is to vomit; however, a moment’s honest refection exposes the fact that while I may abhor the status of ‘expat’, I enjoy the many protections and freedoms it affords me.

This profoundly simple contradiction sharpens my reflections on my experiences this very morning, when I spent a reasonably difficult hour or so buying tickets for my upcoming trip to Los Angeles (during which I discover that when I try to pay on Expedia using my Mexican card, the price automatically doubles). Nevertheless the level of frustration I experience confirming my passage to the land of the free is put into some perspective when I leave my room and head towards the rooftop pool. Leaving the lift one of the maids greets me, asks me if I speak Spanish and also where I’m from. She then asks to speak to me in private.

Yolanda’s Story

I haven’t seen my husband since eight years ago, when I left Miami and came back to Mexico to be with my children. Now he has contacted me and told me that he wants a divorce. He has met a woman, twenty years older than him who tells him she can get him papers if they get married. He says she doesn’t want any money, and that there is nothing going on between them; she says that after the marriage he will get his papers in three months. I don’t know what to do. He insists that the only reason he wants to do this is so that our children will be able to travel to and live in the US when they are older.

Do you think what he says is true? What do you think I should do?

The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argues that nowadays power is measured in mobility. The benefits I enjoy in being able to live in and visit different countries at will constitute profoundly unfair privileges, but this incontrovertible fact is one I find very easy to forget when judging people and situations around me. The sacrifices necessary for Yolanda to guarantee some chance of a future for her family and maintain some some of connection with her husband (who, as I delicately suggest to her the following day when I’ve done a bit of research online, sounds a little bit ingenuo if not a total pendejo) are the result of injustices so absurd that it is hard for me to express to her how abject and awkward they make me feel. As many have commented in the past, one of the damaging and damnable things about privilege is how quickly and insidiously it generates a sense of automatic entitlement.

The exam candidates I interview in the few hours of actual work I do during my visit are mostly trainee sailors, who dream of seeing the world and being able to travel the world with impunity. From 2004–2005 I taught, as it happens, in a maritime university in China, where I tried my best to work my way through the separate, but connected, labyrinth of contradictions which my presence there implied. Over these few days it becomes clear that representatives of what I have gradually and grudgingly been forced to accept is my own government suffer no such moral qualms on their visit to the Middle Kingdom, having cut their way through the maze of ethical considerations and abandoned overnight any notion that the UK has a responsibility to at least pay lip service to a human-rights-and-democracy agenda. In Veracruz I am surprised to see the first Chinese English language school I have ever seen outside China. Media allies of the Cameron regime have themselves seemingly been taking lessons from their Chinese counterparts in how to deal with the opposition, launching a vicious campaign of slander against the Guardian journalist Seamus Milne, who Jeremy Corbyn has had the temerity to try to appoint as Director of Communications without first asking their permission, while also in another transparent attempt to impress their new best friends banning the artist Ai Wei Wei from working in the UK.

China is of course not the only repressive regime the UK Government has been working more closely with of late. In addition to its renewed deep personal friendship with the Democratic Republic of Saudi Arabia, this is also the strictly-not-political Year of Mexico UK; ironically, I’m here in Veracruz on behalf of the main organisations involved in promoting this. If it is fair, as I believe it is, to talk about a global neoliberal regime, I myself am working for it.

The day before I leave I pass through the lobby of my hotel and see another first — a banner advertising $10,000 executive trips by luxury yacht, complete with champagne buffet and shark fishing, which warns potential customers that such trips are ‘subject to climate change’. The following day I wake to a text from Ch. warning of a hurricane on the Pacific coast. Dozily, I look at the bright blue sky out of the window and check the weather for Veracruz online. Nothing — little wind, no hurricane. It is only when I browse twitter for all the latest outrage about Israel and Palestine, the global refugee crisis, Corbyn and Milne, George Osborne’s visit to China and all the rest that I see a post about the biggest hurricane ever, which is headed straight for the opposite coast, the part of the country I am due to fly into that very evening — it is scheduled to arrive in Guadalajara at exactly the same time as I am. On the BBC website there is a startling image making it clear that, while everyone on the coast will die and all the buildings will be destroyed, the bright orange section a little inland is probably the second worst place in the world to be flying to any time soon. Meanwhile on the TV news I hear Enrique Pena Nieto boasting that car sales in Mexico hit 900,000 in the first nine months of the year. Unprecedented hurricanes and record-breaking car sales. I am relieved, in a way, at such clear evidence that the immense contradictions to which I am subject do not only exist in my own head. Subsequently, I delay going to Guadalajara, the destruction caused by Hurricane Patrícia turns out to be a lot less than expected, and I am glad that it is not just me who is enormously lucky.

Of all the possible places to try to sell a dogmatically Leninist newspaper in 2016, the gates of a small, private, right-wing Catholic university is probably not the best location. Leaving work earlier this week I was surprised to encounter an actual 21st Century Bolshevik selling Lotta Comunista (Communist Struggle). Che testardo! The front page featured an actual hammer and sickle and an exhortation to the workers of the world to put down their bloody phones for a minute and UNITE!. Inside there was a closely-written article on US energy policy that featured nary a mention of the changing climate, while page 6 featured a total of 448 individual statistics relating to socio-economic class and voting habits in the USA. At least its position on Sunday’s absurd and suicidal referendum was more sensible than that of the rest of the ‘left’: they recommend that their readers stay at home memorising ‘What is to be done’ rather than bothering to vote. If you’re so inclined you can read your way through the rest of it here.

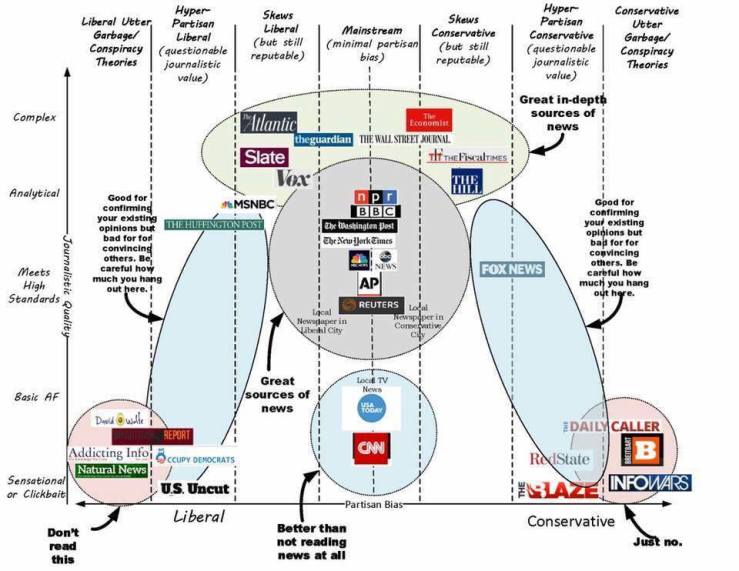

Of all the possible places to try to sell a dogmatically Leninist newspaper in 2016, the gates of a small, private, right-wing Catholic university is probably not the best location. Leaving work earlier this week I was surprised to encounter an actual 21st Century Bolshevik selling Lotta Comunista (Communist Struggle). Che testardo! The front page featured an actual hammer and sickle and an exhortation to the workers of the world to put down their bloody phones for a minute and UNITE!. Inside there was a closely-written article on US energy policy that featured nary a mention of the changing climate, while page 6 featured a total of 448 individual statistics relating to socio-economic class and voting habits in the USA. At least its position on Sunday’s absurd and suicidal referendum was more sensible than that of the rest of the ‘left’: they recommend that their readers stay at home memorising ‘What is to be done’ rather than bothering to vote. If you’re so inclined you can read your way through the rest of it here. young people called Juventude Rebelde (Rebel Youth), which is similar in look, style and content to the kind of publications the Worker’s Revolutionary Party used to try (and fail) to hand out for free. Both newspapers are hard to track down and (after a couple of days of cheap laughs, and once you’ve set aside a few copies as very cheap presents) genuinely not worth the effort. When in the 1990s the US not-an-embassy put up LED screens to broadcast subversive information to the city it must have had quite an impact. In Mozambique – also nominally a Communist country – the national newspapers are remarkably similar in style and content to the cheaper Portuguese tabloids. I once read a very depressing article (it wasn’t supposed to be depressing) about how popular A Bola (The Ball) is in Angola. In some countries, the main journals of record are ones which just report the achievements of government (rather like a lot of local newspapers nowadays in the UK in relation to local councils). In others, the only opposition newspapers are those owned by politically ambitious oligarchs . There are other channels of communication but the absence of a free press makes a country much culturally and socially poorer and less free.

young people called Juventude Rebelde (Rebel Youth), which is similar in look, style and content to the kind of publications the Worker’s Revolutionary Party used to try (and fail) to hand out for free. Both newspapers are hard to track down and (after a couple of days of cheap laughs, and once you’ve set aside a few copies as very cheap presents) genuinely not worth the effort. When in the 1990s the US not-an-embassy put up LED screens to broadcast subversive information to the city it must have had quite an impact. In Mozambique – also nominally a Communist country – the national newspapers are remarkably similar in style and content to the cheaper Portuguese tabloids. I once read a very depressing article (it wasn’t supposed to be depressing) about how popular A Bola (The Ball) is in Angola. In some countries, the main journals of record are ones which just report the achievements of government (rather like a lot of local newspapers nowadays in the UK in relation to local councils). In others, the only opposition newspapers are those owned by politically ambitious oligarchs . There are other channels of communication but the absence of a free press makes a country much culturally and socially poorer and less free. I wanted to write about the new US President’s decision to stop NASA conducting research on the earth’s climate, but word fail me, or maybe I them. Where to begin? It’s too depressing to even link to. It would require a command over language which I don’t possess. Maybe poets and other artists are better placed to develop the new forms of expression which will be able to address this new reality. Or perhaps I should get round to watching ‘Hypernormalisation’.

I wanted to write about the new US President’s decision to stop NASA conducting research on the earth’s climate, but word fail me, or maybe I them. Where to begin? It’s too depressing to even link to. It would require a command over language which I don’t possess. Maybe poets and other artists are better placed to develop the new forms of expression which will be able to address this new reality. Or perhaps I should get round to watching ‘Hypernormalisation’.  It’s a shock to walk into a branch of WalMart to be greeted by the sight of three security guards brandishing the kind of major weaponry currently being used elsewhere to pulverise Isis and their victims to pieces. It’s simultaneously comforting and disconcerting to see that no-one else is paying the slightest attention to their presence, in fact the three Robocop clones are acting just like security guards might elsewhere, except for the fact that they are dressed for World War Three, or possibly Four. I don’t ask. They are strolling around, yawning and playing disconsolately with their Motorolas, eying up the Pick n’ Mix and looking ready to blast into space anyone who looks like they might try to smuggle a 48-inch flatscreen down their trousers. I only popped into the place to buy a tiny bottle of Mezcal to entertain myself with post-work while watching the IT Crowd on Netflix; not finding one, I contemplate the possible consequences of trying to leave empty handed. For the first time in my life I am genuinely apprehensive that someone might shoot me dead unless I purchase some alcohol.

It’s a shock to walk into a branch of WalMart to be greeted by the sight of three security guards brandishing the kind of major weaponry currently being used elsewhere to pulverise Isis and their victims to pieces. It’s simultaneously comforting and disconcerting to see that no-one else is paying the slightest attention to their presence, in fact the three Robocop clones are acting just like security guards might elsewhere, except for the fact that they are dressed for World War Three, or possibly Four. I don’t ask. They are strolling around, yawning and playing disconsolately with their Motorolas, eying up the Pick n’ Mix and looking ready to blast into space anyone who looks like they might try to smuggle a 48-inch flatscreen down their trousers. I only popped into the place to buy a tiny bottle of Mezcal to entertain myself with post-work while watching the IT Crowd on Netflix; not finding one, I contemplate the possible consequences of trying to leave empty handed. For the first time in my life I am genuinely apprehensive that someone might shoot me dead unless I purchase some alcohol. I noticed a couple of years ago when living in a fairly nondescript part of East London, in the kind of Olympically lifeless area where absolutely everyone comes from everywhere else and no-one sticks around for long, that in some parts of the country, and maybe the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to find a shop where get your hands on a physical newspaper. Conversations with my international students confirm this: the regular purchase of a newspaper is increasingly a minority pursuit, an odd and probably slightly quirky habit of people over 35 or so. Younger people inevitably get their news online, if at all – the news might simply consist in what their friends are up to on Facebook or maybe a glance at Google or Yahoo headlines. Given that so much of what we perceive of the world is mediated in some way, what does this imply about our collective experience of a shared reality?

I noticed a couple of years ago when living in a fairly nondescript part of East London, in the kind of Olympically lifeless area where absolutely everyone comes from everywhere else and no-one sticks around for long, that in some parts of the country, and maybe the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to find a shop where get your hands on a physical newspaper. Conversations with my international students confirm this: the regular purchase of a newspaper is increasingly a minority pursuit, an odd and probably slightly quirky habit of people over 35 or so. Younger people inevitably get their news online, if at all – the news might simply consist in what their friends are up to on Facebook or maybe a glance at Google or Yahoo headlines. Given that so much of what we perceive of the world is mediated in some way, what does this imply about our collective experience of a shared reality? Nina Power

Nina Power