I once heard it said that when you move into a new home, one of the first things you should do is get yourself locked out, so as to try to work out how, if you were a burglar dead set on robbing your house, you might go about doing so, all in order to work out how to best protect your property and shore up your possessions. Another game I recently invented, quite inadvertently, is to get yourself locked out not in order to find your way in, but to find your way, as it were, out. After all, in almost all certainty, very, very few of your immediate neighbours are right now planning to rob your house. And getting yourself locked out is a wonderful way to meet your neighbours and find out a little bit about how the society (or, ideally, community) around you works.

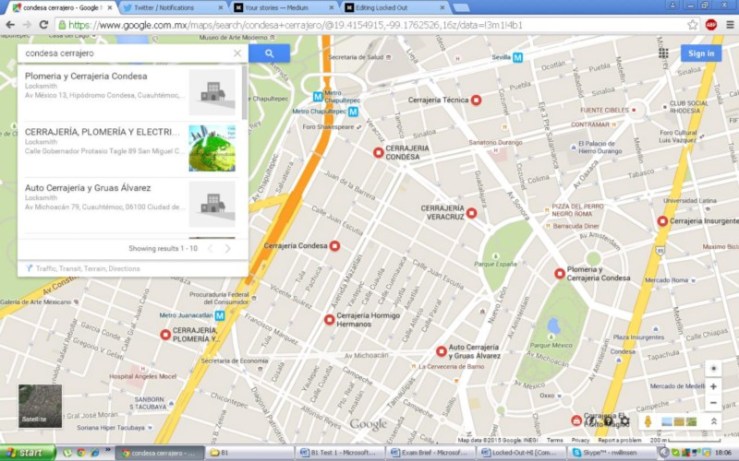

It turns out that, at least in Mexico City, contrary to what you might, quite reasonably, have expected of the place, not everyone needs, or even uses, locks on their doors. Paradoxically, the local locksmith, to whom I swiftly turned in my actually really rather relatively desperate plight, given that I, on the way to the gym, had got myself locked out with no money or phone (and, even more significantly, no keys), two days after my wife, who for comedy reasons also likes to refer to herself as my ‘flatmate’, had flown off to the most racist country on earth for two whole weeks, and given that my landlady, who I managed to contact via Skype having begged my way onto a computer in an extremely obliging local internet café just down the road, didn’t, it transpired, have any keys herself, the locksmith, that one to whom I referred at the start of the sentence, wasn’t actually there, and had left his shop (which doesn’t have a door, let alone a lock) completely unguarded while he went out on a job, but then when he did return, he promised to be round to the flat ‘ahorita’, a word guaranteed to send a chill down the spine of any recently arrived foreigner who tries really hard not to base their knowledge of Mexico on what they’ve read on the internet, but can’t help wondering if that means today, next week, or never, and then (the locksmith) came round five minutes later and, using an instrument the usefulness of which certainly gives one pause for thought (that thought being, my god, it’s really easy to break into houses) he opened the seemingly impregnable door in less time than it takes to put a much-needed full stop at the end of this sentence.

So it turns out that we are lucky to live in a medium-sized village in the centre of what is very probably the largest city on earth. One which, it turns out, unusually for a village, has so many nice places to eat which subsequently turn out to be chain restaurants that you’d start to wonder if when Karl Marx came up with that natty line about the whole world being in chains he might actually have just spent a couple of weeks in Condesa, but one which clearly benefits from a strong sense of, if I can’t quite bring myself to call it social solidarity, certainly abounds in helpfulness and basic good-hearted neighbourliness. Which I must say, and here I risk revealing myself as someone who’s deeply immersed in the third stage of culture shock, is quite refreshing after London. One wonders, and I will return to this shortly, how the UK will deal with the next stage of psychopathic structural adjustment, given that, unlike in a society like Italy, where, as this programme details, young unemployed people will stay with their families, and also unlike (according to David Harvey), in China where it is the ancestral village that provides social support when the state is absent — when a Chinese migrant worker gets ill, they go back to their hometown, in the UK (rejoinder: it seems to me that…) the social fabric, the social safety net that lies underneath the formal state safety net, is extremely frayed. What the UK has in abundance is negative solidarity, a spiteful attitude towards those who are suffering, a contempt for anyone might be seen as a loser or victims. That’s not remotely to claim that compassion and solidarity are absent, but is does mean that, unlike in Spain, where extremely well organized movements have managed in numerous cases to prevent people being kicked out of their homes, in the UK such movements have had very little (one of Russell Brand’s favourite new words coming up!) purchase. In some ways, Mexico (and Spain, and Italy) are probably better societies in which to find yourself locked out of your house, or indeed to be without a home at all, than the UK.