One of the happiest memories of my life is of my 40th birthday get-together in June 2012, when my friend Craig showed me a video on his phone of our former secondary school being smashed to pieces by bulldozers. This realisation of a dream of our teenage years is one of the best presents I have ever received.

One of the happiest memories of my life is of my 40th birthday get-together in June 2012, when my friend Craig showed me a video on his phone of our former secondary school being smashed to pieces by bulldozers. This realisation of a dream of our teenage years is one of the best presents I have ever received.

The reputation of the school had already taken an industrial hammering. Lying on a beach in the Algarve in September 1999, I read a lengthy Guardian report by the investigative journalist Nick Davies (later of ‘Churnalism’ fame). He identified my school as an emblematic victim of early-’80s educational reforms which aimed to remove the comprehensive elements of the education system. It was the perfect example of a school which went wrong in this way. The key year when things really started to plummet downhill like an out-of-control pram was 1983, when they removed streaming. It was also the year I and my cohorts arrived. We were, it seemed, the victims of an experiment – or, at least, of an experiment which had been made to fail by the power of class and a Government ideologically opposed to the principles of comprehensive education. That might explain why we were taught music lessons by a German teacher with an open fascination with Hitler, why we learned French in a science lab whose gas taps some kids could never quite get enough of, and why our Religious Education classes mostly consisted of listening to the teacher’s favourite progressive rock albums, particularly the Ayn ‘Medicare’ Rand-influenced Rush album ‘2112’.

Destruction was a theme of my youth. Sheffield was in the process of deindustrialising and so parts of it were disappearing. A few years ago I came across a BBC documentary from September 1973 (fifteen months after I was born) called ‘All in a Day’, which tracked the daily lives of various locals. Parts of it I recognised but there were some things -fashions, ways of life, institutions – which had already vanished by the time I came into consciousness. Then, when I was 12, I saw the city destroyed by a nuclear explosion.

‘Threads’ was the work of Barry Hines (who also wrote ‘Kes’) and it was shown on the BBC in late 1984. It was a extremely vivid depiction of the total annihilation of the only city I knew. A simmering confrontation in the Middle East between the two superpowers was discussed in increasingly urgent tones on background TVs and the radio, while people very similar to those I knew went about their everyday lives. Some schoolfriends were filmed running down the main shopping street screaming when the four-minute warning went off. My own sister was an extra. She appeared for several centiseconds at the end of a scene in which ashen-faced ‘survivors’ looked though a fence in the radioactive fog at armed soldiers guarding the emergency food supplies. She looked just like she was living through a nuclear holocaust. In reality, of course, she was just terrified she wouldn’t get on TV. The scream she let out on seeing herself was louder than a megaton bomb*.

The irony that South Yorkshire had declared itself a ‘nuclear free-zone’ was much commented-upon, as was the oft-trumpeted (but more often parodied) notion of the ‘Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire’. I grew up in a politically-charged atmosphere. Trips into town to seek out new books and music would inevitably involve getting caught up in furious discussions with left-wing newspaper sellers. I remember the first wave of strikes provoked by Thatcher as part of Nicholas Ridley’s plan to smash to unions to pieces. My father, after a career in haut cuisine, worked at a steel plant from around 1980. When I was ten, in April 1983, he took me on my first protest, outside Cutler’s Hall where Thatcher herself was speaking. Then there was the Miner’s Strike, about which I remember shamefully little.

My vague sense of imminent doom wasn’t helped by the news in 1988 that human civilisation was forcing the world’s temperatures to rise. Whenever I think of the moment I first learned about global warming, I picture the classroom at King Ecgbert’s, in the posher part of town, where I did an A-level in Government and Political Studies. We had a teacher who read to us from The Guardian. The fact that he treated us like adults and obviously enjoyed his job inspired thoughtful, if inchoate, responses. I can see myself in that classroom aged 17; I’m saying something I must have read in the Guardian about feedback loops.

Around that time I was becoming interested in other kinds of loops. In the Leadmill I heard the sparse bleeps and haunting echoes of ‘Sweet Exorcist‘ for the first time. The music released by Fonn and then Warp records followed an established local tradition, using a palette of industrial sounds. In this excellent BBC documentary local musicians of the time talk about how the sounds of the working city forged their sound:

Sheffield was also musically twinned with Dusseldorf, given the influence of Kraftwerk on the Human League and Heaven 17. The dystopian fictions of J.G. Ballard were also an ingredient. Although they never found (or indeed sought) commercial success, Cabaret Voltaire were part of the same wave, along with the Comsat Angels, whose bassist (much more of a pop star than we’d ever be) lived around the corner from us.

Then there was ABC, with their gold lame suits and lush, orchestrated and articulate critiques of Thatcherism. Their flamboyance stood out given that the general tone of life in Sheffield is ‘unimpressed’. There’s an earthiness, a flatness of voice and attitude which contrasts with the hills. Jarvis Cocker is the canonic example of someone who both celebrates and supercedes this. He left the city to broaden his horizons and seek fame but has nevertheless remained loyal. It was his musical map of Sheffield which taught me about the importance of Sheffield’s five rivers in its industrial development. (They probably tried to teach me that in geography classes, but I just remember being lectured about superpigs in the Ruhr Valley by a teacher with a military moustache who spent most of the lessons with his head buried in the Daily Mail.) I thus consider Jarvis to be more of a Sheffielder than I am. Still now my geography of my hometown is shameful. Someone else who knows the city much better than me is the architecture writer Owen Hatherley, who, although he’s not from there, is an articulate and enthusiastic advocate for the Sheffield of the 50’s and 60’s and the pop music culture it eventually inspired. He called his book on Pulp ‘Common’.

The song his title refers to is not my favourite but it is very well-observed. The insult ‘common’ was a very, well, common way of dismissing someone, of asserting one’s claim to a higher rung on the ladder. School was rough, with bullying commonplace, and you just had to learn to cope without appearing ‘soft’. You could detect the resultant hardiness and stoicism in the music. In 1986 the Human League had a transatlantic hit with a song which was clearly not their own. It had been written by Jam and Lewis for Alexander O’Neill or Janet Jackson, and to my ears the spoken section, which was designed to sound breathy and passionate, sounded distinctly sulky, or, as we say in Sheffield, mardy. Actually, when, on what must have been New Year’s Day 1989, me and a friend went to Phil Oakey’s house on Ecclesall Road, he was cheery and welcoming. He made us a cup of tea and we chatted about Barry White.

When I was growing up, the Human League were the local celebrities, our representatives on the national stage, or at least on Top of the Pops. The same was emphatically not true of Def Leppard, at least not in my part of town. They had taken the sounds of heavy steel production in a less interesting direction, to the mid-Atlantic rather than Central Europe. Then, in the ’90s, Sheffield became synonymous with The Full Monty. I’ve watched this film more times than Stewart Lee has seen Scooby Doo. It’s the tale of a group of redundant steelworkers forced by economic circumstances to reinvent themselves as male strippers. One of the most telling moments comes early on, when the wife of one of the main characters pisses in a urinal, thus parodying and asserting a claim over a symbol of male identity. The loss of stable industrial work, with its attendant self-image of the strong male breadwinner, implies a crisis of masculinity. The men have to divest themselves of their ‘male’ identity and try to make the adaption to more ‘feminised’ forms of work, in which bodily image and the ability to adjust to the demands of spectacle are of central concern. The film thus dramatises the fabled shift from heavy industry to the leisure economy and the suspense comes from the question of whether they can make the transition. In fairy tale fashion, they succeed, putting on a strip night and proving they have what it takes to entertain. How they will go on from this one-off performance is unclear, but in neoliberal terms (and this is an emblematically Blairite film), by debasing themselves to the demands of the market they’ve demonstrated they have sufficient will to survive. Although it wasn’t set in Sheffield but nearby, Brassed Off trod very similar ground but was more sombre and angrier in tone. If you add in Billy Elliot there was actually a minor genre of 1990s films in which former industrial zones learnt to strip, play or dance to tunes played by the forces of globalised capitalism.

On another level this is what most cities on the world are trying to do nowadays: to market themselves as cultural destinations. For a brief period Sheffield was home to the ambitious but ill-fated National Centre for Popular Music. The fact that I, for whom pop music was more important than breathing, never got round to visiting it is some indication of how ill-conceived it was. Sheffield also tried to attract sports fans, with the hugely expensive debacle of the World Student Games (who?) in 1991, which the city is, as far as I know, still paying for.

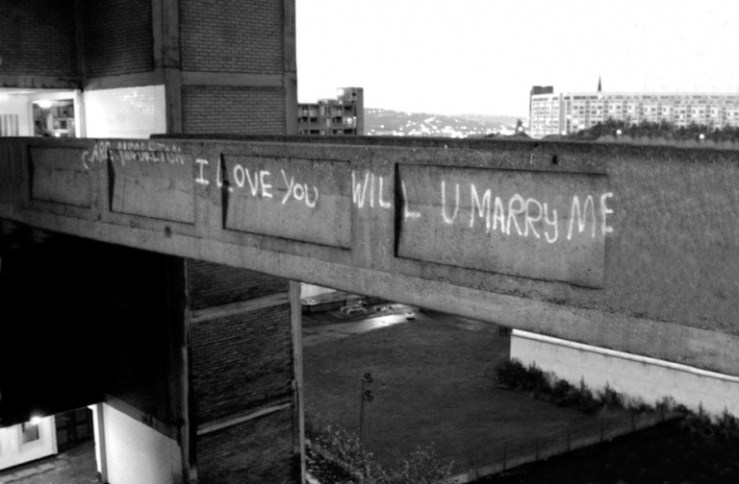

I witnessed the waning of a certain visionary spirit, that which inspired the destruction of the slums and the investment in public housing of the 1950s-60s. Owen Hatherley records that the housing estates in some parts of Gleadless were designed to take advantage of the steep topography and, in the right light, they resemble sunlit Californian hillsides. Park Hill was an absolutely laudable attempt to create decent living conditions close to the centre of the city for ordinary people. It failed, partly through official neglect, but has been widely recognised as a masterpiece of urban design. There was also abundant evidence of a previous generation of patrician municipal idealism in the late 19th Century art galleries, museums and libraries. Then there was the Crucible, which, in addition to snooker championships, put on productions at affordable prices and gave young people to develop an interest in the theatre. Such initiatives were the fruit of an ethic according to which ordinary people should participate fully in the life of the city. One of the great symbols of this principle was the bus fares. As a child I paid 2p to go anywhere in the city. It was a little bit of Cuban-style socialism, one that life immensely more livable. I was lucky to grow up in such a time and place.

Nowadays a different set of priorities prevail. After a number of years the City Council managed to destroy two grubby-but-popular markets (Castle and Sheaf) which played an essential role in the life of the city. They attracted the Wrong Sort of People, principally the poor and the old. The Council demolished the markets and built a more expensive alternative in a totally different part of the city. Doing so is in keeping with an ideological shift: neo-Blairite politicians and their successors want to attract consumers, or preferably hyperconsumers, and what happens to the social fabric as a result is of lesser concern. Thus Sheffield now has some excellent and very large places to eat for those who have some money and want to pretend they have lots: Dubai-style casinos and gargantuan but bland chain steakhouses and Chinese restaurants crowd out the area next to the Town Hall. Also very prominent in the city centre are new blocks of flats, mostly built to accommodate exponentially-multiplying numbers of future generations of foreign university students who, given Theresa May’s antipathy to the UK’s economic survival, will almost certainly never arrive.

One of Sheffield’s least favourite sons, Nick Clegg MP, boasted when he was in government that he would preside over ‘savage cuts’, and the amount of people begging around the city are a testament to just how much he managed to achieve. The desperation caused by the viscous ideologically-inspired attacks on government spending must also have been a factor in the city having voted narrowly for Brexit (by 6,000 votes). Sheffield, dependent on government and EU spending in all its forms, is one city that will suffer enormously as a result. Its attempts to adjust to the new reality of a government agenda driven by psychopathic zeal do direct damage to both the standard of living and the quality of life of the city. As of 2017, the local council has now, in absolute desperation, begun a war against trees, as well as (as far as I can make out) dimming the streetlights. Perhaps they are taking the need to cut down on overheads a little too literally.

My knowledge of Sheffield is dwarfed by the number of things I don’t know, particularly given that I haven’t lived there since I was 18. I’m almost proud to say I don’t know more than a couple of the places mentioned in this recent Guardian article. There’s also the multi-venue music festival Tramlines (for which much credit has to go to a member of the increasingly-less-interesting local superstar band Arctic Monkeys), and the internationally renowned documentary festival.

There are also all sorts of wonderful things in Sheffield that have always been there: the art galleries, the museums, shops like Rhyme and Reason (a treasure trove of books and records I practically lived in when I was young and which, despite the best efforts of the Council, is still hanging on). Hunter’s Bar and the area around Kelham Island still have an abundance of very decent pubs. Sheffield’s parks (and the cafés in the parks) are an absolute joy. The walk from Endcliffe Park through Forge Dam and up Jacob’s Ladder towards the peaks and dales of Derbyshire rivals any holiday jaunt in Tuscany, and the echo of ancient civilisations around Mam Tor and Froggat Edge is just as resonant as symbols of the mysterious beliefs and rituals of lost civilisations at Teotihuacan.

Nevertheless I’m not all that loyal to the city. Neither of my parents is from there and (partly as a result) I don’t sound like a local. There are far more well-informed spokespeople for the city than me. Growing up in Sheffield was pretty much all I knew and it took me until a long time after I’d left to begin to reflect on the geographic and social layout of the city and where I stood in relation to it. Nevertheless it’s the city I’ve spent more time in than anywhere else, and contains numerous people and places who and which will always be among the most precious in my life. I also feel an occasional burst of sentimental pride, mostly from a distance. I can detect traces of deep class solidarity in this video, filmed in a friend’s local pub on the night that Thatcher finally died. I’ll also happily admit to feeling a sense of intense melancholy joy at the end of Synth Britannia at the moment where the LA synth-pomp of ‘Together in Electric Dreams’ kicked in.

But the strongest sense of being part of a community of those born and brought up in Sheffield was in March 2015, when I was part of a group of organisers of a march in London on the theme of Climate Change. Just a few weeks before, on a stormy afternoon, we’d been walking by a river in Derbyshire following several days’ rainfall, admiring the sheer force of the water. The city of Sheffield came into existence as a result of a particular confluence of climatic forces, and in turn played a key role in the development of the industrial age which has come to jeopardise our future as a species. That’s why it felt particular fitting and moving to see on Youtube a group of local choir members gathered at the station to set off for the demonstration, singing an Italian partisan anthem remade for times which will, if we choose to face up to our responsibilities, require similar levels of sacrifice and courage:

(…and then, of course, there’s also this.)

* In an exclusive interview with this website, my sister had the following to say:

I was a 14 year old child star but the rock n roll lifestyle was too much so I had to get a career in the aviation industry when the offers dried up. (The following day).

There were 3 locations that we had to be at & that were at various stages in the aftermath of a nuclear war…the film is on you tube I think x

From LA to San Francisco I take the train. This feels like a novelty because I didn’t know the US still had trains. In Mexico (where I’m living at the moment, viz. November 2015) the train network was broken up and sold off in the early 1990s, and I assumed that the whole train network in the States had long ago suffered a similar fate. It’s one of the many things that surprise me on my inaugural visit to the US.

From LA to San Francisco I take the train. This feels like a novelty because I didn’t know the US still had trains. In Mexico (where I’m living at the moment, viz. November 2015) the train network was broken up and sold off in the early 1990s, and I assumed that the whole train network in the States had long ago suffered a similar fate. It’s one of the many things that surprise me on my inaugural visit to the US. San Francisco feels like a greatest hits of some of the nicest places I’ve ever been to. In Chinatown I have an uncanny sensation that I am back in China. I understand that this is kind of the point of Chinatown, but still. The sights, smells and sounds seem to be those of a place that exists in itself, rather than a mere stopping-off point for tourists.

San Francisco feels like a greatest hits of some of the nicest places I’ve ever been to. In Chinatown I have an uncanny sensation that I am back in China. I understand that this is kind of the point of Chinatown, but still. The sights, smells and sounds seem to be those of a place that exists in itself, rather than a mere stopping-off point for tourists. The layout of the hills reminds me strongly of

The layout of the hills reminds me strongly of  On the way to the Golden Gate park, around the corner from Haight Ashbury Primary School, I stop and watch a game of American football. Americans don’t call it American football, in the same way as the Mexicans don’t talk about Mexican food. It’s a college game, someone explains. I manage

On the way to the Golden Gate park, around the corner from Haight Ashbury Primary School, I stop and watch a game of American football. Americans don’t call it American football, in the same way as the Mexicans don’t talk about Mexican food. It’s a college game, someone explains. I manage  Up at the bridge I enjoy a stunning view across the bay. I’ve missed the famous fog by a couple of months. In any case it’s diminished somewhat over the last couple of years. The climate is, after all, changing.

Up at the bridge I enjoy a stunning view across the bay. I’ve missed the famous fog by a couple of months. In any case it’s diminished somewhat over the last couple of years. The climate is, after all, changing. The next day I spend in Oakland and Berkeley. Mention of Oakland often evokes the famous phrase from Gertrude Stein: “there’s no there there”. Actually, the most powerful association it has for me is with hiphop. Back in the 1990s I listened to a lot of g-funk and was particularly enamoured of a local revolutionary rapper called Paris who was best known for bragadaciously

The next day I spend in Oakland and Berkeley. Mention of Oakland often evokes the famous phrase from Gertrude Stein: “there’s no there there”. Actually, the most powerful association it has for me is with hiphop. Back in the 1990s I listened to a lot of g-funk and was particularly enamoured of a local revolutionary rapper called Paris who was best known for bragadaciously  I get the bus down to Berkeley. My new friends Jan and Steve kindly take me on a walk around the university, which is probably the most climate-aware place on the planet. Because of the drought the grass on the lawns has been replaced by wood shavings, along with a notice explaining why. In the Sciences building there’s an advert for a Survival 101 course (‘the next 50 years will be radically different from anything we have ever known’), a special board for ‘activist jobs’ and more Bernie Sanders graffiti that you can shake an organic placard at. Afterwards we have beer and pizza in their garden and talk about climate awareness strategies.

I get the bus down to Berkeley. My new friends Jan and Steve kindly take me on a walk around the university, which is probably the most climate-aware place on the planet. Because of the drought the grass on the lawns has been replaced by wood shavings, along with a notice explaining why. In the Sciences building there’s an advert for a Survival 101 course (‘the next 50 years will be radically different from anything we have ever known’), a special board for ‘activist jobs’ and more Bernie Sanders graffiti that you can shake an organic placard at. Afterwards we have beer and pizza in their garden and talk about climate awareness strategies. The person who most embodies the radical Bay Area spirit for me is the local writer and activist Rebecca Solnit. Although I’ve insisted here multiple times that climate denial is connected to racism, she points out more clearly and coherently that it is also very much about patriarchy. She’s best-known for writing the essay and subsequent book ‘

The person who most embodies the radical Bay Area spirit for me is the local writer and activist Rebecca Solnit. Although I’ve insisted here multiple times that climate denial is connected to racism, she points out more clearly and coherently that it is also very much about patriarchy. She’s best-known for writing the essay and subsequent book ‘ Another woman I associate with the Bay Area is Oedipa Maas, the heroine of Thomas Pynchon’s novel ‘The Crying of Lot 49’. Looking for an underground postal service which may or may not exist, she follows a series of homeless men through the night as they appear to deposit and collect mail from trash cans. The network may or may not represent another level of reality subjacent to the official America. Oedipa has visions of connections and communities that lie beneath the surface. She sees Californian suburbs laid out like circuit boards and notices arcane symbols used to communicate between those in the know. My father-in-law has a cute theory about how the visions she experiences may be the result of epilepsy. In any case, there’s something extremely prescient about a book published in 1966 anticipating the acid-fuelled flowering of consciousness that was to come.

Another woman I associate with the Bay Area is Oedipa Maas, the heroine of Thomas Pynchon’s novel ‘The Crying of Lot 49’. Looking for an underground postal service which may or may not exist, she follows a series of homeless men through the night as they appear to deposit and collect mail from trash cans. The network may or may not represent another level of reality subjacent to the official America. Oedipa has visions of connections and communities that lie beneath the surface. She sees Californian suburbs laid out like circuit boards and notices arcane symbols used to communicate between those in the know. My father-in-law has a cute theory about how the visions she experiences may be the result of epilepsy. In any case, there’s something extremely prescient about a book published in 1966 anticipating the acid-fuelled flowering of consciousness that was to come. Maybe in the future awareness and empathy will be luxuries, like yachts and, well, houses. In the Bay Area there’s a drought of affordable places to live, which means the cost and scarcity of housing is by far the number one topic of even the most casual conversation. Whereas in London it’s partly the influence of the finance industry making things much more expensive for everyone else, in SF it’s the tech companies. In 2013 local activists started protesting the shuttle buses used by companies like Google to transport their workers to the corporate campuses, like the one described by Dave Eggers in ‘The Circle’. Everyone else is allowed to stay in the city under very stringent conditions. It puts me in mind of an essay I once read by Brazilian sociologists called ‘the return to the medieval city’. In modern cities there are so many exclusions in operation, partly through technology, screening creating invisible walls. The globalised market functions as an particularly efficient repressive tool. Anyone could get removed at any time. Just as undocumented migrants fear the immigration authorities, most people in cities like San Francisco live in terror that their landlords will sell up or raise the rent.

Maybe in the future awareness and empathy will be luxuries, like yachts and, well, houses. In the Bay Area there’s a drought of affordable places to live, which means the cost and scarcity of housing is by far the number one topic of even the most casual conversation. Whereas in London it’s partly the influence of the finance industry making things much more expensive for everyone else, in SF it’s the tech companies. In 2013 local activists started protesting the shuttle buses used by companies like Google to transport their workers to the corporate campuses, like the one described by Dave Eggers in ‘The Circle’. Everyone else is allowed to stay in the city under very stringent conditions. It puts me in mind of an essay I once read by Brazilian sociologists called ‘the return to the medieval city’. In modern cities there are so many exclusions in operation, partly through technology, screening creating invisible walls. The globalised market functions as an particularly efficient repressive tool. Anyone could get removed at any time. Just as undocumented migrants fear the immigration authorities, most people in cities like San Francisco live in terror that their landlords will sell up or raise the rent. Increasing amounts of apartments are given over to Airbnb. The new economy is a battleground. The Bay Area may be one of the places from which field operations are directed, but it is also very vulnerable to their effects. Just a couple of weeks before my visit protestors occupied the company’s headquarters in support of a (subsequently unsuccessful) proposition to limit short-term rentals. The tech industry is a reminder that smart doesn’t mean intelligent. Back in Mexico City I’d noticed that the British Council has a weekly session of TED Talks, open to all its students. These are becoming as ubiquitous in TEFL as they are online. They represent ‘progress’ divorced from politics, entirely mediated by the market, with technology as its stand-in article of faith – after all, it was Friedrich Hayek himself (the father of Neoliberalism) who called the market a kind of technology. The TED ideology is based on a religious faith that the existence of African mobile phone entrepreneurs will somehow save the world. It’s all very slickly packaged and presented, to the extent that The Onion does a very clever

Increasing amounts of apartments are given over to Airbnb. The new economy is a battleground. The Bay Area may be one of the places from which field operations are directed, but it is also very vulnerable to their effects. Just a couple of weeks before my visit protestors occupied the company’s headquarters in support of a (subsequently unsuccessful) proposition to limit short-term rentals. The tech industry is a reminder that smart doesn’t mean intelligent. Back in Mexico City I’d noticed that the British Council has a weekly session of TED Talks, open to all its students. These are becoming as ubiquitous in TEFL as they are online. They represent ‘progress’ divorced from politics, entirely mediated by the market, with technology as its stand-in article of faith – after all, it was Friedrich Hayek himself (the father of Neoliberalism) who called the market a kind of technology. The TED ideology is based on a religious faith that the existence of African mobile phone entrepreneurs will somehow save the world. It’s all very slickly packaged and presented, to the extent that The Onion does a very clever  Down at Fisherman’s Wharf there are actually people fishing. I try to figure out if they’re doing it for food or fun. If it’s sustenance they’re after, they’re in competition for survival with some of the biggest seagulls I’ve ever seen. The scene reminds me of Durban, South Africa, where we saw Indians without rods fishing for whitebait in polluted water. It’s easy to romanticise going off-grid, but surviving outside the walls of the global market is hard. Still, many have no alternative but to escape its dominion and seek out or build alternative communities. José Saramago’s novel ‘The Cave’ is about a shopping mall that dominates every aspect of life in the area around it. Work, food, security and leisure are all increasingly centred on it. At the end the protagonists pack up and drive off the page to an uncertain but more independent future. In the final pages of Pynchon’s ‘Vineland’, set in 1984, Zoyd Wheeler leaves the politically repressive atmosphere of LA and heads up to Northern California, where new communities of hippies and other dissidents are being established. Contrary to the example set by countless backwoods myths and log-cabin yarns, surviving on one’s own is not an option. Cormac McCarthy’s protagonist in ‘The Road’ wanders a devastated post-apocalyptic landscape with a shopping trolley, and the book ends up with a incongruous epiphany which resembles nothing less than an advert for Coca Cola. The motif of the shopping cart put me in mind of the avatar that so often stands in for us on the internet. In McCarthy’s novel there is no more online and no more consumerism, so the future is dead. It is ‘welcome to the desert of the real’ made (barely) flesh. There is no community, with little fellow feeling between the isolated individuals who drift into contact. They are reduced to little more than isolated pixels in a ruined computer game. By contrast, in another of Saramago’s dystopian fictions, ‘Blindness’, the only seeing character literally strings the group of blind people together and manages to preserve some sense of a community in the midst of the shredded social fabric. The final words of the novel are ‘The city was still there’.

Down at Fisherman’s Wharf there are actually people fishing. I try to figure out if they’re doing it for food or fun. If it’s sustenance they’re after, they’re in competition for survival with some of the biggest seagulls I’ve ever seen. The scene reminds me of Durban, South Africa, where we saw Indians without rods fishing for whitebait in polluted water. It’s easy to romanticise going off-grid, but surviving outside the walls of the global market is hard. Still, many have no alternative but to escape its dominion and seek out or build alternative communities. José Saramago’s novel ‘The Cave’ is about a shopping mall that dominates every aspect of life in the area around it. Work, food, security and leisure are all increasingly centred on it. At the end the protagonists pack up and drive off the page to an uncertain but more independent future. In the final pages of Pynchon’s ‘Vineland’, set in 1984, Zoyd Wheeler leaves the politically repressive atmosphere of LA and heads up to Northern California, where new communities of hippies and other dissidents are being established. Contrary to the example set by countless backwoods myths and log-cabin yarns, surviving on one’s own is not an option. Cormac McCarthy’s protagonist in ‘The Road’ wanders a devastated post-apocalyptic landscape with a shopping trolley, and the book ends up with a incongruous epiphany which resembles nothing less than an advert for Coca Cola. The motif of the shopping cart put me in mind of the avatar that so often stands in for us on the internet. In McCarthy’s novel there is no more online and no more consumerism, so the future is dead. It is ‘welcome to the desert of the real’ made (barely) flesh. There is no community, with little fellow feeling between the isolated individuals who drift into contact. They are reduced to little more than isolated pixels in a ruined computer game. By contrast, in another of Saramago’s dystopian fictions, ‘Blindness’, the only seeing character literally strings the group of blind people together and manages to preserve some sense of a community in the midst of the shredded social fabric. The final words of the novel are ‘The city was still there’. There are examples of offline communities which protect those expelled or repulsed by the workings of the Matrix; wherever there aren’t, we have to try and establish them in the face of the confluence of climate breakdown and total corporate control. Climate Camp and Occupy were attempts to set such up places, to establish havens where people could identify and belong. Significantly, Rebecca Solnit spent some of her younger years as part of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common. And although it’s set further down the Californian coast in LA, Pynchon’s ‘Inherent Vice’ (set in 1970, at the waking from the hippy dream presaged in ‘The Crying of Lot 49’) closes with the following passage, one which I personally find of some comfort when contemplating what lies ahead:

There are examples of offline communities which protect those expelled or repulsed by the workings of the Matrix; wherever there aren’t, we have to try and establish them in the face of the confluence of climate breakdown and total corporate control. Climate Camp and Occupy were attempts to set such up places, to establish havens where people could identify and belong. Significantly, Rebecca Solnit spent some of her younger years as part of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common. And although it’s set further down the Californian coast in LA, Pynchon’s ‘Inherent Vice’ (set in 1970, at the waking from the hippy dream presaged in ‘The Crying of Lot 49’) closes with the following passage, one which I personally find of some comfort when contemplating what lies ahead:

These are some fairly disorganised thoughts scribbled in a station and on a train on 24th December last year. I have a bad habit of trying to (in the words of my wife) connect the dots and present a complete and coherent picture of an issue. For reasons that will become clear I don’t want to do that here.

These are some fairly disorganised thoughts scribbled in a station and on a train on 24th December last year. I have a bad habit of trying to (in the words of my wife) connect the dots and present a complete and coherent picture of an issue. For reasons that will become clear I don’t want to do that here.

In a previous life, I lived in Lisbon. I’d already decided it was my favourite city before I’d even set foot there, and in some ways – although I’d never want to go and live there again – it still is.

In a previous life, I lived in Lisbon. I’d already decided it was my favourite city before I’d even set foot there, and in some ways – although I’d never want to go and live there again – it still is.

It sometimes feels as though I have

It sometimes feels as though I have  people to do fun things with. I’d always identified with the unholiness, the foul-

people to do fun things with. I’d always identified with the unholiness, the foul- away from. The proletarian decadence of the 70s and 80s was immortalised in the

away from. The proletarian decadence of the 70s and 80s was immortalised in the wanted to fit in but I felt that my foreignness was never an issue. While in Portugal I had always felt a bit like a guest or a novelty, in Madrid strangers happily chatted away to me at bus stops. I was just a fellow human being who happened to have a funny accent and an occasional habit of saying things that didn’t make much sense. I enjoyed telling people I lived

wanted to fit in but I felt that my foreignness was never an issue. While in Portugal I had always felt a bit like a guest or a novelty, in Madrid strangers happily chatted away to me at bus stops. I was just a fellow human being who happened to have a funny accent and an occasional habit of saying things that didn’t make much sense. I enjoyed telling people I lived  capitals. There are police with guns but we’re used to that because, as I enjoy telling everyone we talk to, We Live In Mexico Now. I don’t feel threatened by the military presence although it strikes me that if I was Middle Eastern maybe I would. There’s a visible increase in the number of homeless people and I notice that the station in Plaza del Sol is now ‘sponsored by Vodafone’. There are more adverts in English, so often the language of exclusivity and exclusion, so it’s encouraging to see a banner hung from the municipal palace reading (in English) ‘Refugees Welcome’. It’s also freezing cold so we seek asylum in a nearby

capitals. There are police with guns but we’re used to that because, as I enjoy telling everyone we talk to, We Live In Mexico Now. I don’t feel threatened by the military presence although it strikes me that if I was Middle Eastern maybe I would. There’s a visible increase in the number of homeless people and I notice that the station in Plaza del Sol is now ‘sponsored by Vodafone’. There are more adverts in English, so often the language of exclusivity and exclusion, so it’s encouraging to see a banner hung from the municipal palace reading (in English) ‘Refugees Welcome’. It’s also freezing cold so we seek asylum in a nearby