The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

H.P. Lovecraft, ‘The Call of Cthulhu’

What would say H.P. Lovecraft say about climate change? His fanatical racism suggests that he would have found a great deal of common ground with Nigel Farage, Steve Bannon and countless others who have made a profession out of denying reality and scapegoating specific groups of human beings for its inconvenient incursions*. But Lovecraft would nonetheless have recognised (and, given his misanthropy, probably welcomed) the climatic transformation that is upon us, and (as the above quote suggests) would have understood our (lack of) reponse to it.

As it happens, he described the Age of the Anthropocene in (joyously unpleasant) detail:

Yet not at first were the great cities of the equator left to the spider and the scorpion. In the early years there were many who stayed on, devising curious shields and armours against the heat and the deadly dryness. These fearless souls, screening certain buildings against the encroaching sun, made miniature worlds of refuge wherein no protective armour was needed. They contrived marvellously ingenious things, so that for a while men persisted in the rusting towers, hoping thereby to cling to old lands till the searing should be over. For many would not believe what the astronomers said, and looked for a coming of the mild olden world again. But one day the men of Dath, from the new city of Niyara, made signals to Yuanario, their immemorially ancient capital, and gained no answer from the few who remained therein. And when explorers reached that millennial city of bridge-linked towers they found only silence. There was not even the horror of corruption, for the scavenger lizards had been swift.

Only then did the people fully realize that these cities were lost to them; know that they must forever abandon them to nature. The other colonists in the hot lands fled from their brave posts, and total silence reigned within the high basalt walls of a thousand empty towns. Of the dense throngs and multitudinous activities of the past, nothing finally remained. There now loomed against the rainless deserts only the blistered towers of vacant houses, factories, and structures of every sort, reflecting the sun’s dazzling radiance and parching in the more and more intolerable heat.

Typically in his stories, something terrible irrupts into our universe. Sometimes it is known by the name Cthulhu, described in ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ as “A monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind”. It’s a non-human force, a possibly divine entity but one which is definitely not benign. Lovecraft drew on previous mythologies in creating his own. In inventing Cthulhu he was influenced by Tennyson’s poem ‘The Kracken‘**.

The first Lovecraftian stories I read were not actually by him, but by various writers about Lisbon. Their stories showed Lisbon as an emblematically Lovecraftian city, with its thousand-year history hiding all sorts of monsters. Some stories drew on the earthquake of 1788, with all that it drowned the city with and all that it buried. Lovecraft’s writing itself is extremely vivid and compelling. It lends itself particularly well to treatment by graphic novelists and is popular with creative misfits like Mark E. Smith of The Fall. The notoriously misanthropic French writer Michel Houllebecq wrote an excellent book on Lovecraft, a writer whose legacy is everpresent both in his work, while the current leading exponent and champion of Weird Fiction is China Miéville (who shares Houellebeqc’s assessment that racism is the driving force in Lovecraft’s fiction, the inspiration for his “poetic trance”).

Another fan was the critical theorist Mark Fisher (aka k-punk). In his final book (‘The Weird and the Eerie’) he writes of the ‘weird intrusion of the outside’ in Lovecraft’s fiction, the ‘traumatising ruptures in the fabric of experience itself’ occasioned by the appearance of phenomena ‘beyond our ordinary experience and conception of space and time itself’.

This echoed with something else I read recently: a book by the novelist and essayist Amitav Ghosh called ‘The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable’ (you can read an extract from it here). In it he argues convincingly that the modern novel is underpinned by a philosophy of gradualism. The novels of great authors such as Austen, Chatterjee and Flaubert are set in reduced and largely self-contained social worlds in which it is taken for granted that everyday life is largely predictable and ordered. The standard plot involves a disturbance from inside or outside in response to which the world of the novel reconfigures and resettles itself.

While in the time before the modern novel, popular texts such as ‘The Arabian Nights’ and ‘The Decameron‘ “proceeded by leaping blithely from one exceptional event to another”, when we enter the worlds depicted in realist fiction we are conditioned to regard sudden cataclysmic events as contrived and implausible. This is partly because the real subject of such novels is not so much the events themselves but rather the details and stylings of the bourgeois worlds that the characters inhabit. Thus miraculous and exceptional events which overturn that world do not get a look in.

We can also see something like this in the form of soap operas. In their later years domestic dramas such as ‘Brookside’ and ‘Emmerdale’ were regularly ridiculed for using such attention-grabbing contrivances as plane crashes, fires and terrorist attacks. Such intrusions breaks the rules of realist narrative, which say that this is a stable, self-centred and largely predictable world.

How would a soap opera set in the Phillipines deal with a hurricane like Haiyan? Such increasingly commmon catastrophes undermine the dependable world of the telenovela. An interesting example of a partly anthropocenic soap opera is ‘Jane the Virgin’, which regularly features extreme weather events in order to provide far-fetched plot twists, and which works because it’s a post-modern (as in tongue-in cheek and preposterous) pastiche of the format itself.

Soap operas and the modern novel dramatise everyday life in societies which are presented as essentially stable. They are not able to portray a world which is more vulnerable to sudden cataclysm and in which events cannot be explained without making explicit our dependence on other times and places. One thing that makes Lovecraft’s fiction so frightening and unusual is its depiction of non-human forces, intrusions which challenge our agency and control as a species, and consciousnesses with which we cannot communicate or negotiate.

Of course, with what is usually referred to as genre fiction – principally fantasy and science fiction – magical and miraculous elements occur. Long before Climate Change became public knowledge JG Ballard was speculating about what an overheating planet would be like in works like ‘Drowned World’ and ‘The Drought’. The main proponent of the mini-genre apparently known as ‘cli-fi’ is of course Margaret Atwood, who has used the conventions of Science Fiction to depict a climate-induced dystopia in ‘Oryx and Crake’, ‘The Year of the Flood’ and (although I haven’t read it yet) ‘MaddAdam’.

Then there is the genre of adventure fiction with its interest in time travel, including century-old classics by Jules Vernes and HG Wells. Such works particularly inspired children’s fiction which was often set in a unchanging world whose social forms were so static no one even grows old. Thomas Pynchon parodied this form in ‘Against the Day’, which does qualify as a climate change novel given that it features Lovecraftian passages such as this:

“We are here among you as seekers of refuge from our present—your future—a time of worldwide famine, exhausted fuel supplies, terminal poverty—the end of the capitalistic experiment. Once we came to understand the simple thermodynamic truth that Earth’s resources were limited, in fact soon to run out, the whole capitalist illusion fell to pieces. Those of us who spoke this truth aloud were denounced as heretics, as enemies of the prevailing economic faith. Like religious Dissenters of an earlier day, we were forced to migrate, with little choice but to set forth upon that dark fourth-dimensional Atlantic known as Time.”

Anthopocenic fiction will need to be considerably more radical than what still passes for fantasy. While it purports a world entirely other, ‘Lord of the Rings’ depicts a comforting world based on a conservative mythology. It may be that ‘Game of Thrones’ (which I’ve never seen) falls into the same category, in the sense that for all its shocking elements it conveys a fundamentally reactionary view of the universe, like an even more atavistic Downton Abbey. It may also be the case that the new form of soap opera which that programme belongs to – longform Netflix/Amazon dramas which develop over several dozen (or in some cases several hundred) hours – is able to accommodate new kinds and levels of human experience. Although I haven’t talked here about cinema (one film that bears repeated attention in this context is ‘Children of Men’), it seems clear to me that the worlds presented in dystopian Hollywood blockbusters such as ‘Hunger Games’ and ‘Mad Max’ are not actually predictions but prescriptions of a future world which is short on resources but high on aggression and conflict. In the modern age it is partly through bigscreen fictions that we learn how to be human.

Will we (in the words of Lovecraft) “go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age”? The latter is what such films are selling. It’s no accident that the tropes they draw upon (dispensible peasants, bows and arrows, mortar and pestle) are largely medieval. Our cities already resemble those of the Middle Ages, with all their exclusions inscribed into both the visible and invisible frameworks. Lovecraft’s misanthropy is as addictive and hugely entertaining as his racism is vile; let’s hope (no matter how horrifyingly compelling the phantasmagoric soap opera that is anthropocenic politics is) that atavistic tyrants such as Trump and Putin do not turn out to be the manifestations of Cthulhu in (barely) human form that they appear to be.

*This gave the title to one of China Miéville’s novels.

**Although relativising Lovecraft’s virulent racism appears to be a sub-hobby for a few of his fans, this is not an article about that subject. Please leave your comments requesting that his racism not be discussed at the end of this (excellent) piece instead.

I’ve argued repeatedly here that if you want to understand the rise of the global far-right movement you have to put climate denial at the centre of the picture. The chief protagonist in the conspiracy in the decades-long campaign to forestall action on global warming in order to protect corporate profits is Exxon Mobil.

I’ve argued repeatedly here that if you want to understand the rise of the global far-right movement you have to put climate denial at the centre of the picture. The chief protagonist in the conspiracy in the decades-long campaign to forestall action on global warming in order to protect corporate profits is Exxon Mobil.

From LA to San Francisco I take the train. This feels like a novelty because I didn’t know the US still had trains. In Mexico (where I’m living at the moment, viz. November 2015) the train network was broken up and sold off in the early 1990s, and I assumed that the whole train network in the States had long ago suffered a similar fate. It’s one of the many things that surprise me on my inaugural visit to the US.

From LA to San Francisco I take the train. This feels like a novelty because I didn’t know the US still had trains. In Mexico (where I’m living at the moment, viz. November 2015) the train network was broken up and sold off in the early 1990s, and I assumed that the whole train network in the States had long ago suffered a similar fate. It’s one of the many things that surprise me on my inaugural visit to the US. San Francisco feels like a greatest hits of some of the nicest places I’ve ever been to. In Chinatown I have an uncanny sensation that I am back in China. I understand that this is kind of the point of Chinatown, but still. The sights, smells and sounds seem to be those of a place that exists in itself, rather than a mere stopping-off point for tourists.

San Francisco feels like a greatest hits of some of the nicest places I’ve ever been to. In Chinatown I have an uncanny sensation that I am back in China. I understand that this is kind of the point of Chinatown, but still. The sights, smells and sounds seem to be those of a place that exists in itself, rather than a mere stopping-off point for tourists. The layout of the hills reminds me strongly of

The layout of the hills reminds me strongly of  On the way to the Golden Gate park, around the corner from Haight Ashbury Primary School, I stop and watch a game of American football. Americans don’t call it American football, in the same way as the Mexicans don’t talk about Mexican food. It’s a college game, someone explains. I manage

On the way to the Golden Gate park, around the corner from Haight Ashbury Primary School, I stop and watch a game of American football. Americans don’t call it American football, in the same way as the Mexicans don’t talk about Mexican food. It’s a college game, someone explains. I manage  Up at the bridge I enjoy a stunning view across the bay. I’ve missed the famous fog by a couple of months. In any case it’s diminished somewhat over the last couple of years. The climate is, after all, changing.

Up at the bridge I enjoy a stunning view across the bay. I’ve missed the famous fog by a couple of months. In any case it’s diminished somewhat over the last couple of years. The climate is, after all, changing. The next day I spend in Oakland and Berkeley. Mention of Oakland often evokes the famous phrase from Gertrude Stein: “there’s no there there”. Actually, the most powerful association it has for me is with hiphop. Back in the 1990s I listened to a lot of g-funk and was particularly enamoured of a local revolutionary rapper called Paris who was best known for bragadaciously

The next day I spend in Oakland and Berkeley. Mention of Oakland often evokes the famous phrase from Gertrude Stein: “there’s no there there”. Actually, the most powerful association it has for me is with hiphop. Back in the 1990s I listened to a lot of g-funk and was particularly enamoured of a local revolutionary rapper called Paris who was best known for bragadaciously  I get the bus down to Berkeley. My new friends Jan and Steve kindly take me on a walk around the university, which is probably the most climate-aware place on the planet. Because of the drought the grass on the lawns has been replaced by wood shavings, along with a notice explaining why. In the Sciences building there’s an advert for a Survival 101 course (‘the next 50 years will be radically different from anything we have ever known’), a special board for ‘activist jobs’ and more Bernie Sanders graffiti that you can shake an organic placard at. Afterwards we have beer and pizza in their garden and talk about climate awareness strategies.

I get the bus down to Berkeley. My new friends Jan and Steve kindly take me on a walk around the university, which is probably the most climate-aware place on the planet. Because of the drought the grass on the lawns has been replaced by wood shavings, along with a notice explaining why. In the Sciences building there’s an advert for a Survival 101 course (‘the next 50 years will be radically different from anything we have ever known’), a special board for ‘activist jobs’ and more Bernie Sanders graffiti that you can shake an organic placard at. Afterwards we have beer and pizza in their garden and talk about climate awareness strategies. The person who most embodies the radical Bay Area spirit for me is the local writer and activist Rebecca Solnit. Although I’ve insisted here multiple times that climate denial is connected to racism, she points out more clearly and coherently that it is also very much about patriarchy. She’s best-known for writing the essay and subsequent book ‘

The person who most embodies the radical Bay Area spirit for me is the local writer and activist Rebecca Solnit. Although I’ve insisted here multiple times that climate denial is connected to racism, she points out more clearly and coherently that it is also very much about patriarchy. She’s best-known for writing the essay and subsequent book ‘ Another woman I associate with the Bay Area is Oedipa Maas, the heroine of Thomas Pynchon’s novel ‘The Crying of Lot 49’. Looking for an underground postal service which may or may not exist, she follows a series of homeless men through the night as they appear to deposit and collect mail from trash cans. The network may or may not represent another level of reality subjacent to the official America. Oedipa has visions of connections and communities that lie beneath the surface. She sees Californian suburbs laid out like circuit boards and notices arcane symbols used to communicate between those in the know. My father-in-law has a cute theory about how the visions she experiences may be the result of epilepsy. In any case, there’s something extremely prescient about a book published in 1966 anticipating the acid-fuelled flowering of consciousness that was to come.

Another woman I associate with the Bay Area is Oedipa Maas, the heroine of Thomas Pynchon’s novel ‘The Crying of Lot 49’. Looking for an underground postal service which may or may not exist, she follows a series of homeless men through the night as they appear to deposit and collect mail from trash cans. The network may or may not represent another level of reality subjacent to the official America. Oedipa has visions of connections and communities that lie beneath the surface. She sees Californian suburbs laid out like circuit boards and notices arcane symbols used to communicate between those in the know. My father-in-law has a cute theory about how the visions she experiences may be the result of epilepsy. In any case, there’s something extremely prescient about a book published in 1966 anticipating the acid-fuelled flowering of consciousness that was to come. Maybe in the future awareness and empathy will be luxuries, like yachts and, well, houses. In the Bay Area there’s a drought of affordable places to live, which means the cost and scarcity of housing is by far the number one topic of even the most casual conversation. Whereas in London it’s partly the influence of the finance industry making things much more expensive for everyone else, in SF it’s the tech companies. In 2013 local activists started protesting the shuttle buses used by companies like Google to transport their workers to the corporate campuses, like the one described by Dave Eggers in ‘The Circle’. Everyone else is allowed to stay in the city under very stringent conditions. It puts me in mind of an essay I once read by Brazilian sociologists called ‘the return to the medieval city’. In modern cities there are so many exclusions in operation, partly through technology, screening creating invisible walls. The globalised market functions as an particularly efficient repressive tool. Anyone could get removed at any time. Just as undocumented migrants fear the immigration authorities, most people in cities like San Francisco live in terror that their landlords will sell up or raise the rent.

Maybe in the future awareness and empathy will be luxuries, like yachts and, well, houses. In the Bay Area there’s a drought of affordable places to live, which means the cost and scarcity of housing is by far the number one topic of even the most casual conversation. Whereas in London it’s partly the influence of the finance industry making things much more expensive for everyone else, in SF it’s the tech companies. In 2013 local activists started protesting the shuttle buses used by companies like Google to transport their workers to the corporate campuses, like the one described by Dave Eggers in ‘The Circle’. Everyone else is allowed to stay in the city under very stringent conditions. It puts me in mind of an essay I once read by Brazilian sociologists called ‘the return to the medieval city’. In modern cities there are so many exclusions in operation, partly through technology, screening creating invisible walls. The globalised market functions as an particularly efficient repressive tool. Anyone could get removed at any time. Just as undocumented migrants fear the immigration authorities, most people in cities like San Francisco live in terror that their landlords will sell up or raise the rent. Increasing amounts of apartments are given over to Airbnb. The new economy is a battleground. The Bay Area may be one of the places from which field operations are directed, but it is also very vulnerable to their effects. Just a couple of weeks before my visit protestors occupied the company’s headquarters in support of a (subsequently unsuccessful) proposition to limit short-term rentals. The tech industry is a reminder that smart doesn’t mean intelligent. Back in Mexico City I’d noticed that the British Council has a weekly session of TED Talks, open to all its students. These are becoming as ubiquitous in TEFL as they are online. They represent ‘progress’ divorced from politics, entirely mediated by the market, with technology as its stand-in article of faith – after all, it was Friedrich Hayek himself (the father of Neoliberalism) who called the market a kind of technology. The TED ideology is based on a religious faith that the existence of African mobile phone entrepreneurs will somehow save the world. It’s all very slickly packaged and presented, to the extent that The Onion does a very clever

Increasing amounts of apartments are given over to Airbnb. The new economy is a battleground. The Bay Area may be one of the places from which field operations are directed, but it is also very vulnerable to their effects. Just a couple of weeks before my visit protestors occupied the company’s headquarters in support of a (subsequently unsuccessful) proposition to limit short-term rentals. The tech industry is a reminder that smart doesn’t mean intelligent. Back in Mexico City I’d noticed that the British Council has a weekly session of TED Talks, open to all its students. These are becoming as ubiquitous in TEFL as they are online. They represent ‘progress’ divorced from politics, entirely mediated by the market, with technology as its stand-in article of faith – after all, it was Friedrich Hayek himself (the father of Neoliberalism) who called the market a kind of technology. The TED ideology is based on a religious faith that the existence of African mobile phone entrepreneurs will somehow save the world. It’s all very slickly packaged and presented, to the extent that The Onion does a very clever  Down at Fisherman’s Wharf there are actually people fishing. I try to figure out if they’re doing it for food or fun. If it’s sustenance they’re after, they’re in competition for survival with some of the biggest seagulls I’ve ever seen. The scene reminds me of Durban, South Africa, where we saw Indians without rods fishing for whitebait in polluted water. It’s easy to romanticise going off-grid, but surviving outside the walls of the global market is hard. Still, many have no alternative but to escape its dominion and seek out or build alternative communities. José Saramago’s novel ‘The Cave’ is about a shopping mall that dominates every aspect of life in the area around it. Work, food, security and leisure are all increasingly centred on it. At the end the protagonists pack up and drive off the page to an uncertain but more independent future. In the final pages of Pynchon’s ‘Vineland’, set in 1984, Zoyd Wheeler leaves the politically repressive atmosphere of LA and heads up to Northern California, where new communities of hippies and other dissidents are being established. Contrary to the example set by countless backwoods myths and log-cabin yarns, surviving on one’s own is not an option. Cormac McCarthy’s protagonist in ‘The Road’ wanders a devastated post-apocalyptic landscape with a shopping trolley, and the book ends up with a incongruous epiphany which resembles nothing less than an advert for Coca Cola. The motif of the shopping cart put me in mind of the avatar that so often stands in for us on the internet. In McCarthy’s novel there is no more online and no more consumerism, so the future is dead. It is ‘welcome to the desert of the real’ made (barely) flesh. There is no community, with little fellow feeling between the isolated individuals who drift into contact. They are reduced to little more than isolated pixels in a ruined computer game. By contrast, in another of Saramago’s dystopian fictions, ‘Blindness’, the only seeing character literally strings the group of blind people together and manages to preserve some sense of a community in the midst of the shredded social fabric. The final words of the novel are ‘The city was still there’.

Down at Fisherman’s Wharf there are actually people fishing. I try to figure out if they’re doing it for food or fun. If it’s sustenance they’re after, they’re in competition for survival with some of the biggest seagulls I’ve ever seen. The scene reminds me of Durban, South Africa, where we saw Indians without rods fishing for whitebait in polluted water. It’s easy to romanticise going off-grid, but surviving outside the walls of the global market is hard. Still, many have no alternative but to escape its dominion and seek out or build alternative communities. José Saramago’s novel ‘The Cave’ is about a shopping mall that dominates every aspect of life in the area around it. Work, food, security and leisure are all increasingly centred on it. At the end the protagonists pack up and drive off the page to an uncertain but more independent future. In the final pages of Pynchon’s ‘Vineland’, set in 1984, Zoyd Wheeler leaves the politically repressive atmosphere of LA and heads up to Northern California, where new communities of hippies and other dissidents are being established. Contrary to the example set by countless backwoods myths and log-cabin yarns, surviving on one’s own is not an option. Cormac McCarthy’s protagonist in ‘The Road’ wanders a devastated post-apocalyptic landscape with a shopping trolley, and the book ends up with a incongruous epiphany which resembles nothing less than an advert for Coca Cola. The motif of the shopping cart put me in mind of the avatar that so often stands in for us on the internet. In McCarthy’s novel there is no more online and no more consumerism, so the future is dead. It is ‘welcome to the desert of the real’ made (barely) flesh. There is no community, with little fellow feeling between the isolated individuals who drift into contact. They are reduced to little more than isolated pixels in a ruined computer game. By contrast, in another of Saramago’s dystopian fictions, ‘Blindness’, the only seeing character literally strings the group of blind people together and manages to preserve some sense of a community in the midst of the shredded social fabric. The final words of the novel are ‘The city was still there’. There are examples of offline communities which protect those expelled or repulsed by the workings of the Matrix; wherever there aren’t, we have to try and establish them in the face of the confluence of climate breakdown and total corporate control. Climate Camp and Occupy were attempts to set such up places, to establish havens where people could identify and belong. Significantly, Rebecca Solnit spent some of her younger years as part of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common. And although it’s set further down the Californian coast in LA, Pynchon’s ‘Inherent Vice’ (set in 1970, at the waking from the hippy dream presaged in ‘The Crying of Lot 49’) closes with the following passage, one which I personally find of some comfort when contemplating what lies ahead:

There are examples of offline communities which protect those expelled or repulsed by the workings of the Matrix; wherever there aren’t, we have to try and establish them in the face of the confluence of climate breakdown and total corporate control. Climate Camp and Occupy were attempts to set such up places, to establish havens where people could identify and belong. Significantly, Rebecca Solnit spent some of her younger years as part of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common. And although it’s set further down the Californian coast in LA, Pynchon’s ‘Inherent Vice’ (set in 1970, at the waking from the hippy dream presaged in ‘The Crying of Lot 49’) closes with the following passage, one which I personally find of some comfort when contemplating what lies ahead:

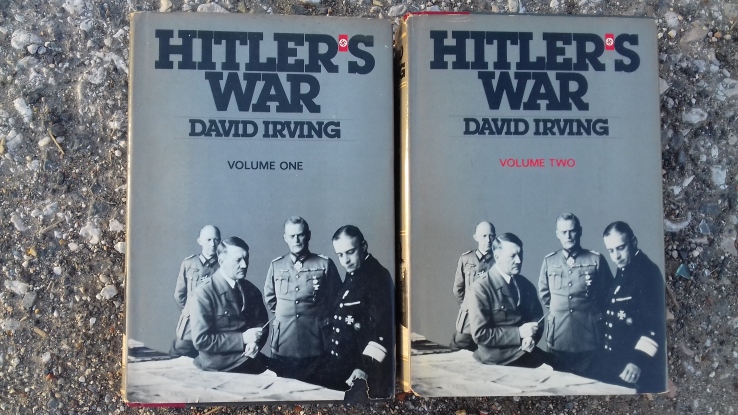

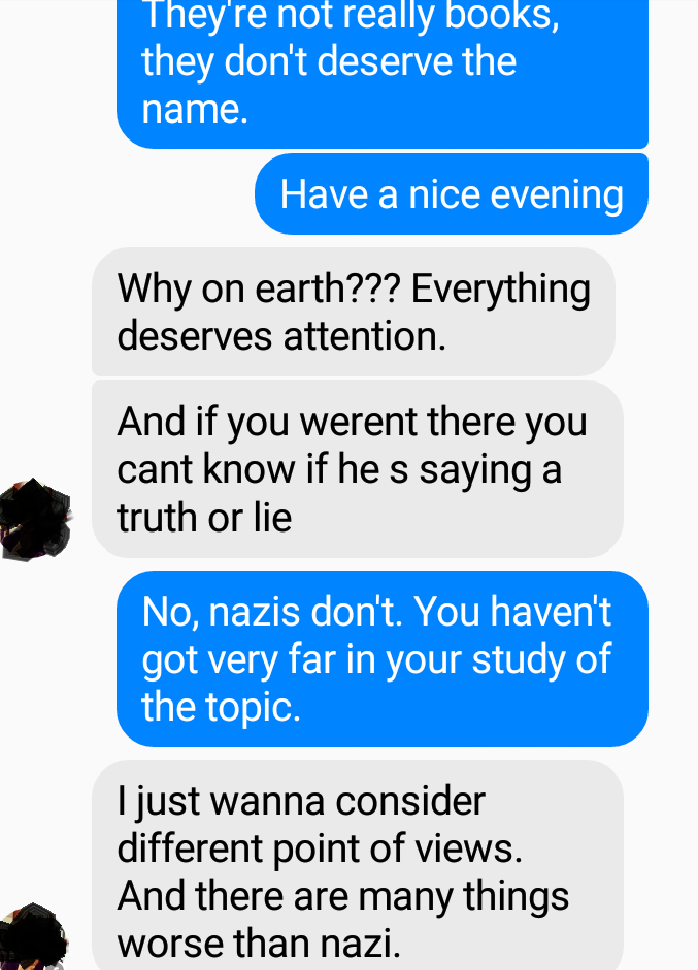

I miss the days before Kindles and iPods, when you could get to know someone better by browsing through their book and music collections. Our Dutch friend Merel, at whose house we spend New Year’s Eve, has a good variety of recent fiction and books on sustainable development and the like. I’m a little taken aback to see on her shelves quite a range of books on dictators and fascism, including two by the disgraced Hitler apologist David Irving. Thankfully it turns out they belong to her landlord.

I miss the days before Kindles and iPods, when you could get to know someone better by browsing through their book and music collections. Our Dutch friend Merel, at whose house we spend New Year’s Eve, has a good variety of recent fiction and books on sustainable development and the like. I’m a little taken aback to see on her shelves quite a range of books on dictators and fascism, including two by the disgraced Hitler apologist David Irving. Thankfully it turns out they belong to her landlord.

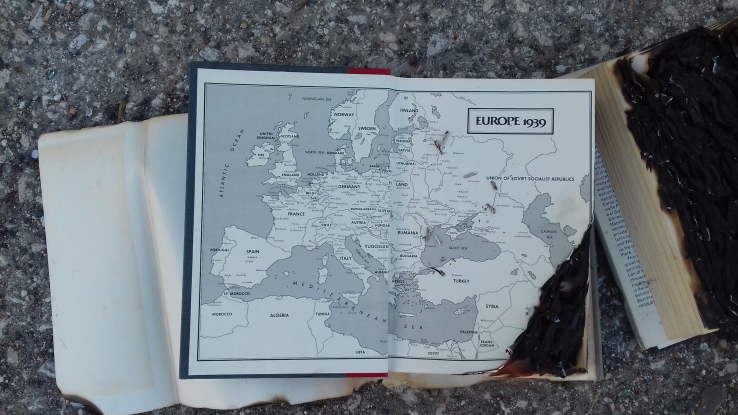

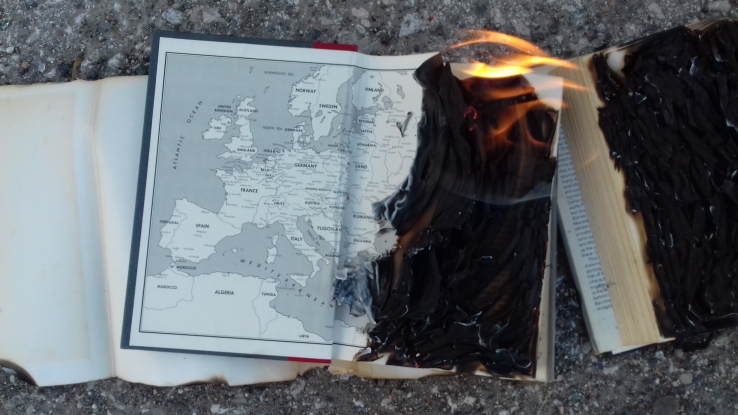

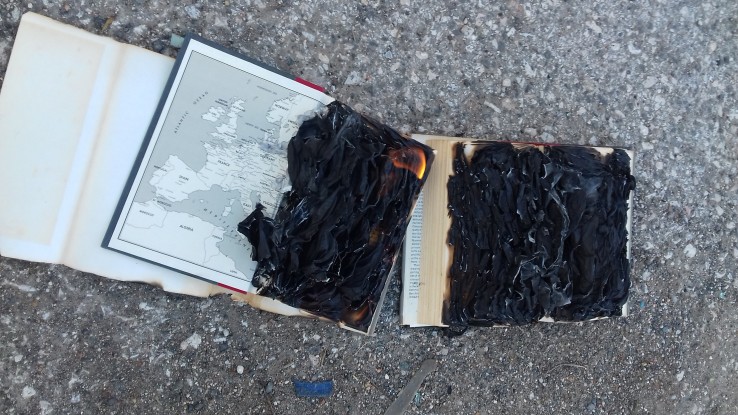

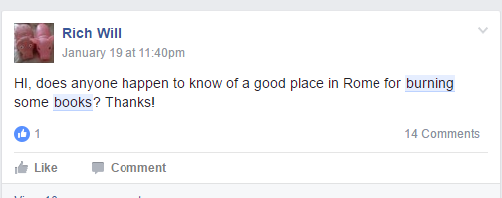

Someone in the Facebook group had suggested a far-off part of town crummy enough that few would be bothered by the sight of someone burning some books, but I didn’t really want to drag a one-week-old-baby across Rome and end up getting us both arrested for arson. Instead I thought of a largely abandoned area round the corner, next to the river, so I could get the whole thing out of the way in half an hour and not neglect my parental responsibilities. As it happens the area isn’t uninhabited; there’s a community of gypsies scattered along a stretch of the Tiber. Elsewhere on Facebook I read about the impending destruction of a similar settlement in Napoli, where my wife was born. The

Someone in the Facebook group had suggested a far-off part of town crummy enough that few would be bothered by the sight of someone burning some books, but I didn’t really want to drag a one-week-old-baby across Rome and end up getting us both arrested for arson. Instead I thought of a largely abandoned area round the corner, next to the river, so I could get the whole thing out of the way in half an hour and not neglect my parental responsibilities. As it happens the area isn’t uninhabited; there’s a community of gypsies scattered along a stretch of the Tiber. Elsewhere on Facebook I read about the impending destruction of a similar settlement in Napoli, where my wife was born. The