Recently, during a class discussion about acceptable questions to ask a recent acquaintance, I asked my students if it was okay to ask a relative stranger if they were a member of the Communist Party. I expected them to answer, as I think most Westerners would do, that it was not okay, because discussing politics in this way might lead to unwanted disagreement. The consensus was, however, that it might be okay if you needed something done and the person concerned might be able to help you.

Recently, during a class discussion about acceptable questions to ask a recent acquaintance, I asked my students if it was okay to ask a relative stranger if they were a member of the Communist Party. I expected them to answer, as I think most Westerners would do, that it was not okay, because discussing politics in this way might lead to unwanted disagreement. The consensus was, however, that it might be okay if you needed something done and the person concerned might be able to help you.

What, then, is the Chinese Communist Party? It is certainly Chinese, but there are very few people who would these days characterise its politics as related to the theories of Karl Marx or the efforts of the Bolsheviks to establish a classless society in anything other than a purely rhetorical sense.

But is it, in fact, a political party? Not in the sense that it competes on an ideological battleground with other political forces. The Communist Party is supposed to be an all-encompassing organisation that renders other points of view obsolete. In practice, of course, instead of encompassing other points of view it ferociously silences them. The right of political debate is restricted solely to proven Party members.

More recently some of those Party members have been more vociferous about the kind of society they want to create. Known as the New Left, they look to a more social democratic model, influenced as far as I can tell by European societies which in the post-war period established a social pact between the trade unions, the Government and the employers. This social pact enabled Germany and Scandinavian societies to develop sustainably and to provide an enviable social safety net for their citizens.

Could such a model be applied in China? Well, I think it does need to be remembered that the social pact which apparently functioned so well in those societies from which China’s New Left are so keen to draw inspiration, was itself the product of struggle; the development of social welfare systems and the inclusion of trade unions in social bargaining was not something freely granted from above, but was based on a recognition of their very real and proven power in relatively free societies. However, could the Chinese Communist Party begin to make serious adjustments and reforms which at least ameliorated the worst effects of rampant capitalism on people’s lives and provided some kind of social safety net for those most in need?

This is a hugely complex issue which I think will come to dominate international debate about China in the coming years. According to an optimistic point of view, as expressed by one of the discussion panel members on this BBC radio programme, what China wants and needs to do is to copy the example of the Labour Party in Britain, with the added difficulty of doing so while remaining in power.

To start with, I think that the example of the British Labour Party is hugely misleading. Firstly, because the project of reforming the Labour Party was carried out by the pro-market leadership in opposition to the wishes of a very large proportion of the more left-wing socially concious Party members. In the case of China, it is the left-wing party members who are the advocates of change against the wishes of the dominant right-wing pro-market Party leadership.

Another problem with the analogy is that, although superficially attractive, it ignores the recent history of the Communist Party. The Communist Party has been making a rightward-bound ideological journey more or less ever since the early nineteen-sixties, when in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward a certain amount of market reforms were introduced as a precursor to the start of the abandonment of Communist ideology by Deng Xiao Ping in the late nineteen-seventies. This was of course following the outburst of out-and-out autocracy of Mao’s ‘Great Purge’. Over ten years ago the disavowal of the wish for an equitable society was formalised by Jiang Zemin, who in his bizarrely-named ‘Three Represents’ theory welcomed back into the party all those people – ‘rightists’, capitalists and so on – who had been persecuted throughout the nineteen-fifties and sixties.

However, the journey the CCP has been taking has nothing to do with an increasing sense of social justice; quite the opposite, in fact. What it says clearly is: “If you can’t beat them, join them”. Now when the CCP is so keen to welcome representatives of the Guomindang to China, it seems that there is very little to distinguish the two in political terms.

So can the Chinese Communist Party reform itself into a Social Democratic Party with Chinese Characteristics? As I say, it’s a huge area of debate and I think the arguments will run and run, but I just want to draw two brief analogies.

The first is the Catholic Church, which in the nineteen-sixties attempted through the Vatican II doctrine to get rid of some of it’s more backward thinking on social issues. I think that at the time a lot of Catholic clergy took heart from the changes that were made, and it led directly to what we call ‘Liberation Theology’, the promotion of social as well as heavenly justice.

So what happened? Now we have a church which seems to be more reactionary than ever, promoting the development of AIDS throughout the second and third world, arrogantly refusing to deal with the firestorm of paedophile allegations which threaten to drive more and more moderate Catholics away from the church, and whose congregations are now asked to worship an ex-Nazi Pope, as if to emphasise that there is nothing worldly about his power and that he cannot be challenged by mere mortals. So what happened?

I think the main reason has to do with power. The Catholic Church is driven first and foremost by the need to protect its own existence. Its authority derives from core beliefs which are reactionary and superstitious, and to suggest that they can be adapted to suit social realities is I think to call into question that authority. A Catholic church genuinely and actively committed to challenging poverty and injustice would be unable to sustain its own power and wealth.

As I said at the start, my students don’t seem to really regard the Chinese Communist Party as a political party as we might understand it, but as an organisation of power, privilege and prestige. Throughout the country party officials and to a certain extent ordinary Party members are allowed to run amok: charging peasants illegal taxes, running up restaurant bills for thousands of dollars, stuffing their pockets with public cash, paying thugs to beat villagers off their own land, building up huge unpayable debts with banks, everywhere doing favours for people they like and making life difficult or impossible for those who they don’t. And doing all this with relative impunity – who is going to stand in their way? Other Party members?

It is only a tiny amount of cases of corruption that we ever get to hear about. As far as I can see, corruption and abuse is the rule and not the exception. My second analogy, then, is the Mafia.

In the Godfather Part 2 Michael Corleone is young, idealistic and determined not to follow the example of his father. He is going to clean up his family businesses and make them respectable. So what happens? I don’t want to spoil it for anyone, but it is the Mafia we are talking about here after all. How can you reform an organisation that is based on criminal corruption, on the systematic hoarding and abuse of power? Maybe we can conclude that what Michael wants doesn’t really change, but as a leading member of the organisation he has a crucial job to do: Protect the Family.

I don’t think that China’s New Left are in any way insincere about their project of bringing social justice to China. But I think they’re misguided and possibly naive about the organisation they are members of. Unfortunately I think their efforts only go to provide window dressing for the Party leadership – it enables them to say ‘Look! We have open debate inside the Party! No need for dissidents! Don’t you see how wrong Wei Jingsheng and all those other foreign agents were? China is marching straight down the road to democracy all by itself and we don’t need any advice or criticism from outside!’.

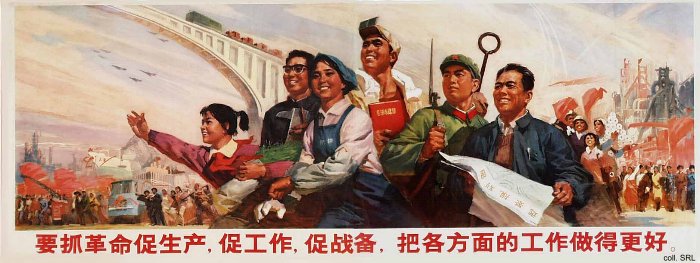

Is there anyone alive today who still sees China as a grey, hostile country, closed off to the rest of the world, where everyone sports Chairman Mao hats and rides bicycles while chanting passages from the Little Red Book? Certainly anyone who has visited the country in the last 20 or so years is genuinely surprised by the size and number of the skyscrapers, the traffic jams and the brand-new shopping centres selling the same fashions as in the West.The Chinese are proud of their new country, and pleased that people come to visit and see the results of the changes for themselves. Foreigners visiting or living in China are encouraged to spread the word, to use the benefit of their broadmindedness and wisdom to impart the truth to others abroad who ‘don’t understand’ how much things have changed. And the authorities also see their own job as ‘educating’ foreigners about the new China. According to Sun Jiazheng, the head of the Ministry of Culture:

Is there anyone alive today who still sees China as a grey, hostile country, closed off to the rest of the world, where everyone sports Chairman Mao hats and rides bicycles while chanting passages from the Little Red Book? Certainly anyone who has visited the country in the last 20 or so years is genuinely surprised by the size and number of the skyscrapers, the traffic jams and the brand-new shopping centres selling the same fashions as in the West.The Chinese are proud of their new country, and pleased that people come to visit and see the results of the changes for themselves. Foreigners visiting or living in China are encouraged to spread the word, to use the benefit of their broadmindedness and wisdom to impart the truth to others abroad who ‘don’t understand’ how much things have changed. And the authorities also see their own job as ‘educating’ foreigners about the new China. According to Sun Jiazheng, the head of the Ministry of Culture: About 10 or so years ago I used to do a weekly show on pirate radio in Dublin. A lot of it consisted of me ranting about whatever was going through my head, interspersed with playing whatever bits of music took my fancy. It being a pirate station, it wasn’t like we conducted regular audience research, and apart from a closely-written postcard accusing me of being an ‘English cesspit’, the only feedback I remember receiving was comments coaxed out of friends, telling me that it was ‘quite funny’, ‘not quite as funny as that other time’ and asking me where I’d got that track from, the one about mescalin that went dum dum THUMP dumdum THUMP THUMP THUMP….A lot of the time it felt a lot like hard work without much more than its own reward.

About 10 or so years ago I used to do a weekly show on pirate radio in Dublin. A lot of it consisted of me ranting about whatever was going through my head, interspersed with playing whatever bits of music took my fancy. It being a pirate station, it wasn’t like we conducted regular audience research, and apart from a closely-written postcard accusing me of being an ‘English cesspit’, the only feedback I remember receiving was comments coaxed out of friends, telling me that it was ‘quite funny’, ‘not quite as funny as that other time’ and asking me where I’d got that track from, the one about mescalin that went dum dum THUMP dumdum THUMP THUMP THUMP….A lot of the time it felt a lot like hard work without much more than its own reward.

Recently, during a class discussion about acceptable questions to ask a recent acquaintance, I asked my students if it was okay to ask a relative stranger if they were a member of the Communist Party. I expected them to answer, as I think most Westerners would do, that it was not okay, because discussing politics in this way might lead to unwanted disagreement. The consensus was, however, that it might be okay if you needed something done and the person concerned might be able to help you.

Recently, during a class discussion about acceptable questions to ask a recent acquaintance, I asked my students if it was okay to ask a relative stranger if they were a member of the Communist Party. I expected them to answer, as I think most Westerners would do, that it was not okay, because discussing politics in this way might lead to unwanted disagreement. The consensus was, however, that it might be okay if you needed something done and the person concerned might be able to help you.