Here are two sets of coincidences that begin in the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and end, for the time being, in Rome.

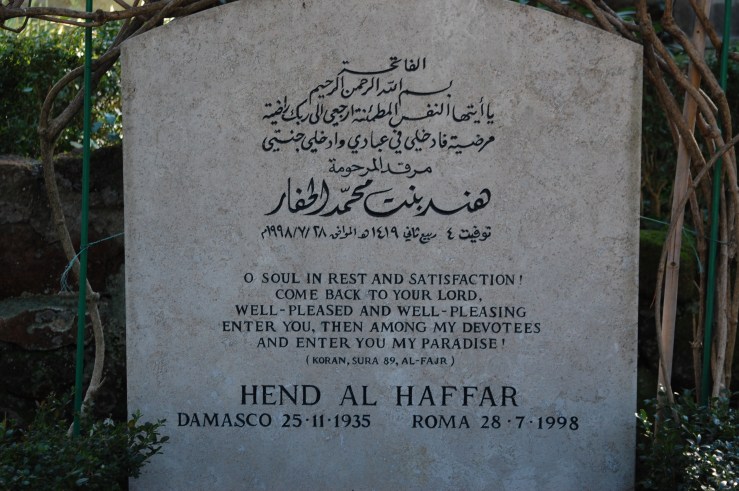

In December 2015 I went to an exhibition by Emily Jacir on the life and murder of her fellow Palestinian Wael Zuaiter, a translator who took refuge in Rome but was murdered by Mossad in 1972. There were photos of his bookshelves containing a number of books I’d also read and quotes from his own books from which it’s clear he was an intriguing and exemplary engaged intellectual. At the time of his death he was translating ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ into Italian. His letters also show him to be an unusually perceptive and trenchant critique of imperialism, as well as a firm opponent of political violence. He was tracked down by the Israeli secret services and murdered on his own doorstep.

I’d been thinking about Rome as a safe haven. At the time we were living in Mexico but there were reports that the security situation in the areas where we lived was breaking down, with a new wave of threats against local restaurants and bars and a couple of murders on our doorstep. (I wrote about this here.) Around the same time I was reading a novel by Tomasso Pincio. I’d noticed this writer in bookshops because his nome de plume is a deliberate reference (and also adjacent on the bookshelf) to my favourite American novelist, Thomas Pynchon.

The novel I was reading is called ‘Cinacittà’ and is a murder story set in a future Rome which, due to global warming, has been abandoned by the locals and is now inhabited solely by Chinese people. Its epigraph is a quote from an ‘American writer’ taken from Federico Fellini’s film ‘Roma’, which I hadn’t yet seen. It talks about Rome as “a wonderful place to witness the end of the world”.

In August 2016 I go back to the Whitechapel Gallery and browse the bookshop. This is something I usually prevent myself from doing as, like the LRB and ICA bookshops, the Whitechapel is like a crackhouse for me. I usually come across at least six books which I know I have to read immediately. Sure enough, there’s one I’ve seen before but realise is exactly the book I need to read right now: ‘The Hatred of Poetry’, by Ben Lerner. It’s a book by a poet about how difficult and in some ways how annoying poetry is. I’ve been actively struggling with poetry for the last couple of years. Just up the road, in Limehouse, I did a series of courses which involved discussing poems and then trying to write them ourselves. The first part I loved, the second continually defeated me. When it came to writing, no matter how much expert guidance I received or exercises I did, I didn’t really understand what a poem is.

Lener argues that it’s easy to love poetry, but individual poems themselves are often too much of a challenge. Poems aspire to the condition of poetry, but always fail. I like his tone of voice and wonder what his poems are like. As it happens, the name Ben Lerner rings a bell. I see that he was the author of a 2012 novel called ‘Leaving the Atocha Station’; as I once lived in Madrid, I’d noticed the title but never thought about reading it. Reading reviews of the novel on my phone I realise it’s right up my street. It’s about a pretentious young expat poet living in Spain and pretending not to be American, smoking spliffs and looking down at other foreigners “whose lives were structured by attempting to appear otherwise”. I can relate to that, and the description of his prose as ‘precise’ appeals to me.

I start reading the poetry book as I walk down the street. In the first couple of pages he mentions his favourite poet, one which (as he correctly predicts) I’ve never heard of, which makes me wonder who mine is. One name that immediately springs to mind is Luke Kennard, whose work has the advantage of being hugely entertaining (one of my favourite words when it comes to poems). I should read this guy’s novel, I think. As it happens I’m heading down to the South Bank anyway and I have a Waterstones voucher card that’s been in my wallet for months and which I can’t remember if I’ve ever used. My day now has more of a purpose to it and I speed up my stroll towards Trafalgar Square.

It turns out that the card in my wallet only has £1.01 on it, which means I really should think twice about also buying Lerner’s second novel, but it’s described as “a near-perfect piece of literature” and was chosen as ‘Book of the Year’ by 15 reputable publications.

Now I’ve got three new books, all by the same author. I walk across to The Royal Festival Hall, where I’m meeting a friend at 5. It’s only 4.15, so I decide to kill time in Foyles. The first book I see when I walk in is a volume of poetry by Ben Lerner, a compendium of his three collections. I have no intention whatsoever of buying it, but I pick it up because I’m keen to see what his poetry is like. The inner cover has a quote from Luke Kennard: “I look forward to Ben Lerner’s poetry the way I used to anticipate a new record by my favourite band.” Right next to the quote is the price: £14.99. If I buy it I will have all the published work by my new favourite author, one by whom I haven’t yet read more than a few pages. I snap it shut and make my way to the cash desk.

It occurred to me some time ago that it’s deeply ironic that although I grew up antagonostic to capitalism on the whole, I also spent my youth obsessing over sales charts. If The Jesus and Mary Chain burst into the pop charts at number 11, or if New Order managed to get onto Top of the Pops, it felt like a personal victory, and I would feel downcast for days if The Smiths failed to get into the top ten. There was an article by Simon Frith in the Pet Shop Boys 1989 tour programme arguing that their music celebrates and mourns that moment of melancholy just before you hand over the money for a new record or just before you fall in love, when you know that disappointment is inevitable. That’s the nature of commerce: it involves an emotional investment in something you know won’t satisfy you. Given that the emotional and intellectual payback of novels and films is deeper than so much else we consume, capitalism promotes their addictive qualities. There’s also the aspect of cultural capital, that we place cultural products in our personal shop windows to attract others – or, less cynically, that they allow us to identify (and be identified by) others who have shared often very intimate and personal experiences. In other words, we also use them as a form of bonding with others of our species, which is the very much the point of being alive.

I find it hard to track down the film ‘Roma’ online. In any case, I first need to rewatch ‘La Dolce Vita’, and then ‘8 1/2’, which I can’t remember ever having seen. There’s also Bertolucci’s and Antonioni’s films to catch up on. Some of these things I can find online but in most cases I need to get the DVDs. Luckily there are lots of market stalls selling €3 copies of classic films, the ones previously sold as promotions with newspapers. In Pigneto I chat to the owners and other browsers, who recommend a whole bunch of things I’ve never heard of. I quickly build up a collection of Scuola, Moretti and Pasolini. Then it’s a question of finding the time to watch it all.

The (very) English writer Geoff Dyer lived in Rome and suffered from depression. He writes about it in ‘Out of Sheer Rage’, his chronicle of his failed attempt to write a book about DH Lawrence which is also, finally, a book about DH Lawrence. He describes staring for hours at his TV, wondering if he should turn it on. Rome initially strikes me as a strange place to get depressed, but then I work out he must have been here in winter. Winter in Rome is (increasingly) short but very grey, with a cigarette ash atmosphere coating the city. Dyer then recounts how he escaped from his depression: he took an interest in it. He started thinking and reading about depression, and then had to leave the house to track down books to learn more. His mood lifted as he became part of the city, its bookshops, literary events and galleries.

Another writer I hugely admire (Nick Currie, aka Momus), has written persuasively and with his customary eloquence about how, in a globalised and digitally connected world, you can live the same life pretty much anywhere. He writes about moving from Berlin to Osaka and continuing exactly the same lifestyle. My own is essentially the same whether in London, Mexico City or Rome- pretty much wherever Amazon delivers, in fact. I noticed that my English language students in London were generally happy with their accommodation as long as it featured basic furniture and services, few disturbances and a very fast internet connection. It was by far the absence of the latter that generated the most complaints.

My own youth fed on record shops, bookshops and libraries. I was lucky to grow up in a age and a city in which there was an abundance of all three. Of course, I’m privileged now too. I can buy books if I want and I have time to wander round and enjoy what cities have to offer. I’ve lived in a succession of capital cities, all with a huge range of bookshops. Nevertheless, I miss record shops and haven’t felt the need to go to my local library since I lived in London. Like almost everybody on the planet I am far too dependent on the Internet for my cultural life.

The internet gives you access to everything. It has an infinite number of channels. But without a purpose it can be a medium for depression. After too much time online I sometimes feel like a polar bear in a zoo, pacing back and forth, scrolling and clicking aimlessly to the point where I lose all sense of what I want and who I am. Our physical selves thrive on fresh air, trees, company, exchanges of words, glances and embraces. I need to get out of the house. Luckily in Rome (we finally move here in September 2016) I have no internet on my phone and a whole city to explore. After a couple of weeks I finally track down one of my favourite bookshops. Invito alla Lettura is a dusty clutter of crumbling hardbacks, stacks of old editions of magazines, fascist pamphlets from the 30s, and a pleasant café (in Mexico it would be called a cafebrería) . Or rather, it was. It apparently shut down in April 2016 after nearly 25 years. From the owner of the Almost Corner bookshop in Trastevere I learn that food outlets are pushing out more established business, just like in London.

Humans will always need on-the-spot food and drink, but books, music and films you can get hold of online. There will always be a demand for places where you can go and browse them and maybe meet and fall in love with other people who share the same enthusiasms, but that doesn’t mean the market will necessarily provide such places. Bookshops and record shops were never primarily about buying, much more about communing with others who share a need for new ideas, impressions, experiences. I hope that when my baby daughter comes of age there will still be places where she can go to explore and celebrate whatever books and music she comes to love and, in the company of others, discover more. At least Rome has such an abundance of excellent bookshops, from Altroquando via Fahrenheit 451 to Minimum Fax, that it’s reasonable to hope that it will hold out longer against the forces of the global market as marshalled on the internet. Forse Gore Vidal, as in so many other things, aveva ragione.

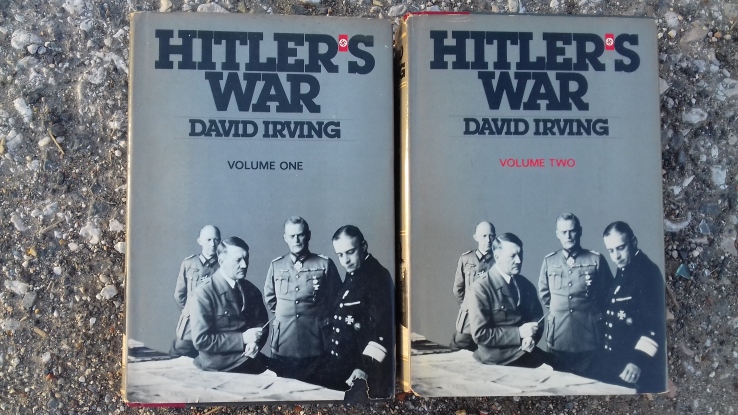

I miss the days before Kindles and iPods, when you could get to know someone better by browsing through their book and music collections. Our Dutch friend Merel, at whose house we spend New Year’s Eve, has a good variety of recent fiction and books on sustainable development and the like. I’m a little taken aback to see on her shelves quite a range of books on dictators and fascism, including two by the disgraced Hitler apologist David Irving. Thankfully it turns out they belong to her landlord.

I miss the days before Kindles and iPods, when you could get to know someone better by browsing through their book and music collections. Our Dutch friend Merel, at whose house we spend New Year’s Eve, has a good variety of recent fiction and books on sustainable development and the like. I’m a little taken aback to see on her shelves quite a range of books on dictators and fascism, including two by the disgraced Hitler apologist David Irving. Thankfully it turns out they belong to her landlord.

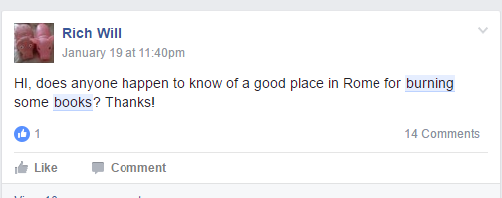

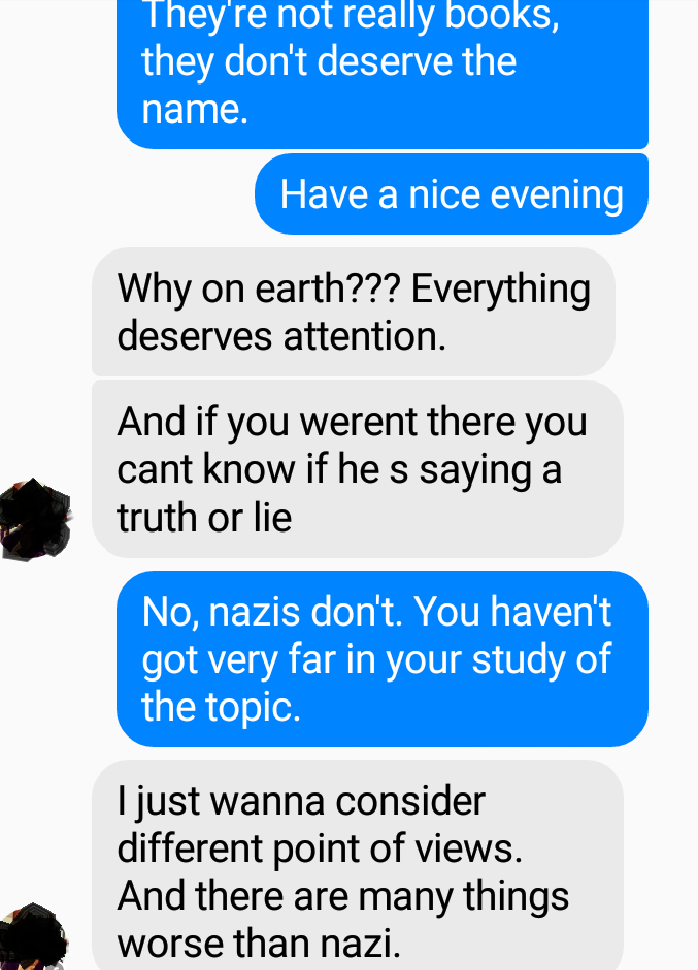

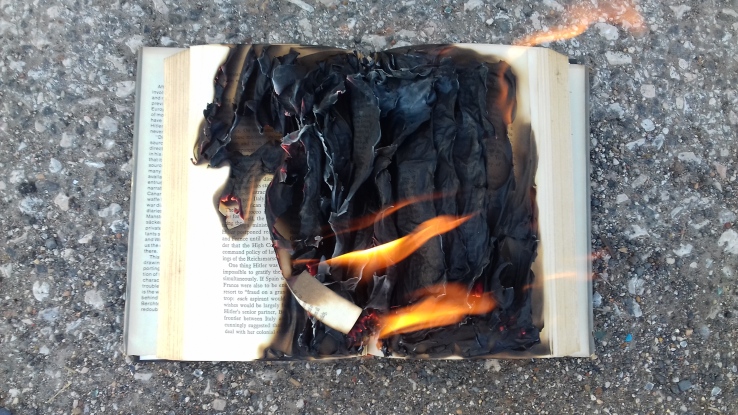

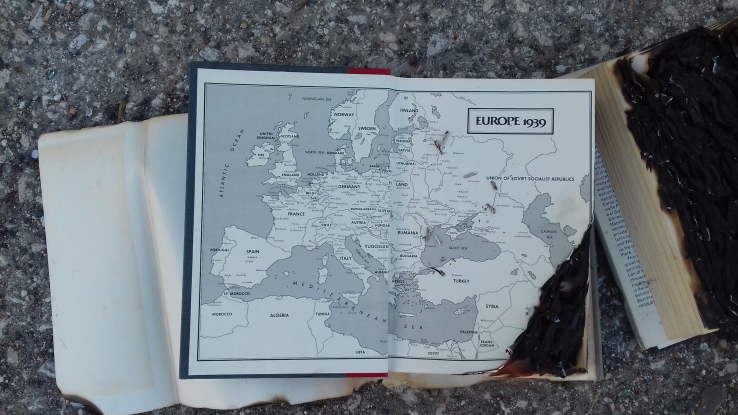

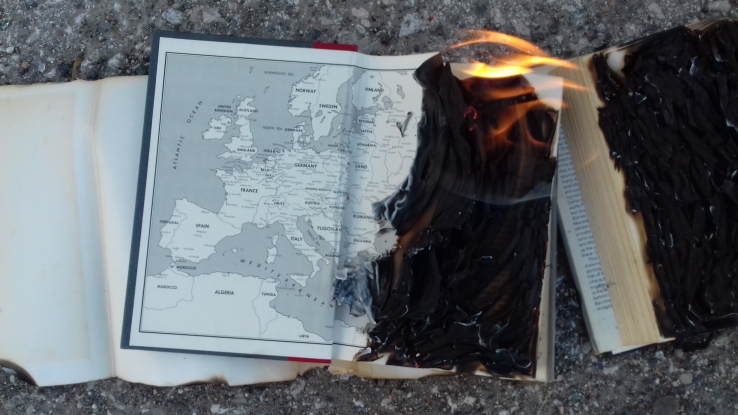

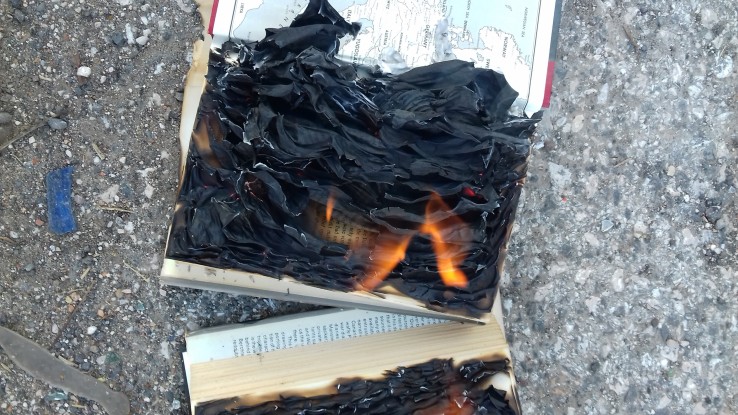

Someone in the Facebook group had suggested a far-off part of town crummy enough that few would be bothered by the sight of someone burning some books, but I didn’t really want to drag a one-week-old-baby across Rome and end up getting us both arrested for arson. Instead I thought of a largely abandoned area round the corner, next to the river, so I could get the whole thing out of the way in half an hour and not neglect my parental responsibilities. As it happens the area isn’t uninhabited; there’s a community of gypsies scattered along a stretch of the Tiber. Elsewhere on Facebook I read about the impending destruction of a similar settlement in Napoli, where my wife was born. The

Someone in the Facebook group had suggested a far-off part of town crummy enough that few would be bothered by the sight of someone burning some books, but I didn’t really want to drag a one-week-old-baby across Rome and end up getting us both arrested for arson. Instead I thought of a largely abandoned area round the corner, next to the river, so I could get the whole thing out of the way in half an hour and not neglect my parental responsibilities. As it happens the area isn’t uninhabited; there’s a community of gypsies scattered along a stretch of the Tiber. Elsewhere on Facebook I read about the impending destruction of a similar settlement in Napoli, where my wife was born. The

These are some fairly disorganised thoughts scribbled in a station and on a train on 24th December last year. I have a bad habit of trying to (in the words of my wife) connect the dots and present a complete and coherent picture of an issue. For reasons that will become clear I don’t want to do that here.

These are some fairly disorganised thoughts scribbled in a station and on a train on 24th December last year. I have a bad habit of trying to (in the words of my wife) connect the dots and present a complete and coherent picture of an issue. For reasons that will become clear I don’t want to do that here. “The way people look at you and mutter about you on the bus or train, as though you’re dangerous. That would never have happened in the ’80s. Now if you want to rent a house, you’ll get a viewing appointment over the phone alright, but as soon as you get there and they see you’re black, you’ll either get told ‘it’s already gone’ or quite simply ‘the neighbours don’t want to live next to foreigners’. It’s become quite normal for people to admit they’re ‘anti-foreign’ and talk about it freely. They don’t differentiate between migrants and nationals with foreign parents.” (

“The way people look at you and mutter about you on the bus or train, as though you’re dangerous. That would never have happened in the ’80s. Now if you want to rent a house, you’ll get a viewing appointment over the phone alright, but as soon as you get there and they see you’re black, you’ll either get told ‘it’s already gone’ or quite simply ‘the neighbours don’t want to live next to foreigners’. It’s become quite normal for people to admit they’re ‘anti-foreign’ and talk about it freely. They don’t differentiate between migrants and nationals with foreign parents.” ( “In July, in Quinto di Treviso, Northeast Italy, residents and far-right militants broke into flats destined to receive asylum-seekers, took the furniture outside and set it on fire, leading the authorities to move the asylum-seekers to another location.” (

“In July, in Quinto di Treviso, Northeast Italy, residents and far-right militants broke into flats destined to receive asylum-seekers, took the furniture outside and set it on fire, leading the authorities to move the asylum-seekers to another location.” ( “Akram, a 17-year-old Kurdish boy from Iraq, hid under a truck on the ferry from Greece to Italy for 18 hours without food or water. When he arrived in Italy, the police locked him in a small room on the ferry and sent him right back to Greece.”

“Akram, a 17-year-old Kurdish boy from Iraq, hid under a truck on the ferry from Greece to Italy for 18 hours without food or water. When he arrived in Italy, the police locked him in a small room on the ferry and sent him right back to Greece.”  “Mayor Alberto Panfilio said calm had been restored at the center, where up to 1,500 people have been placed in a facility originally meant for 15 migrants.” (

“Mayor Alberto Panfilio said calm had been restored at the center, where up to 1,500 people have been placed in a facility originally meant for 15 migrants.” ( “Four Eritrean girls, aged 16 and 17, said that adult men constantly harassed them. Bilen, 17, said men “come when we sleep, they tell us they need to have sex. They follow us when we go to take a shower. All night they wait for us… They [the police, the staff] know about this, everybody knows the problem, but they do nothing.”” (

“Four Eritrean girls, aged 16 and 17, said that adult men constantly harassed them. Bilen, 17, said men “come when we sleep, they tell us they need to have sex. They follow us when we go to take a shower. All night they wait for us… They [the police, the staff] know about this, everybody knows the problem, but they do nothing.”” ( “Yodit cupped her hands in prayer as we dialed. Those hands flew to her mouth as she realized that the phone – and her prayers – had been answered. It was the first time she had spoken to her mother since being rescued at sea and taken to Italy two weeks before.” (

“Yodit cupped her hands in prayer as we dialed. Those hands flew to her mouth as she realized that the phone – and her prayers – had been answered. It was the first time she had spoken to her mother since being rescued at sea and taken to Italy two weeks before.” ( “Kaiser Tetteh was from Ghana. He was kidnapped and imprisoned for three months in a makeshift jail in Libya by a smuggling gang. “Kidnapping is normal. If you are in a taxi they will kidnap you, they will take everything from you.” He said he witnessed the killing of 69 people in Libya during an escape attempt from the prison. “All the time you don’t sleep,” he said. “Everyone has guns. Even kids have guns.” Lucky told us he did not mind where he was resettled in Europe. “I’m a beggar, I don’t have any choice. I just want protection. I just need freedom.”” (

“Kaiser Tetteh was from Ghana. He was kidnapped and imprisoned for three months in a makeshift jail in Libya by a smuggling gang. “Kidnapping is normal. If you are in a taxi they will kidnap you, they will take everything from you.” He said he witnessed the killing of 69 people in Libya during an escape attempt from the prison. “All the time you don’t sleep,” he said. “Everyone has guns. Even kids have guns.” Lucky told us he did not mind where he was resettled in Europe. “I’m a beggar, I don’t have any choice. I just want protection. I just need freedom.”” ( ““It is not easy to live here illegally,” Lisa, one of the volunteers told me. “I don’t know if people really want this, sleeping in the park or not having a job. “We think people are coming here because of war and violence, not because we are kind. We are doing something very human. We tell them where to go, where to eat and try to give them advice. We don’t want them to be illegal.”” (

““It is not easy to live here illegally,” Lisa, one of the volunteers told me. “I don’t know if people really want this, sleeping in the park or not having a job. “We think people are coming here because of war and violence, not because we are kind. We are doing something very human. We tell them where to go, where to eat and try to give them advice. We don’t want them to be illegal.”” ( “Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi on Sunday called for a concerted international effort to block people-traffickers after the reported deaths of up to 700 migrants in the latest sinking in the Mediterranean. “We are asking not to be left alone,” Renzi told reporters after an impromptu cabinet meeting, adding that he wanted an emergency meeting of European Union leaders to be held this week to discuss the mounting migrant crisis. Renzi underlined that search and rescue missions alone were not sufficient to save lives. He said the problem could only be solved by preventing the criminal activity of people trafficking and stopping migrant boats from leaving Libya.” (

“Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi on Sunday called for a concerted international effort to block people-traffickers after the reported deaths of up to 700 migrants in the latest sinking in the Mediterranean. “We are asking not to be left alone,” Renzi told reporters after an impromptu cabinet meeting, adding that he wanted an emergency meeting of European Union leaders to be held this week to discuss the mounting migrant crisis. Renzi underlined that search and rescue missions alone were not sufficient to save lives. He said the problem could only be solved by preventing the criminal activity of people trafficking and stopping migrant boats from leaving Libya.” ( “I left Ethiopia because of the political situation. I’m Oromo and in 1991 there was conflict between Tigrinya and Oromo. My grandfather and my father fought for the Oromo. Later, my father was arrested and my brother shot dead at university by the government. In Ethiopia if you are Oromo you can’t do anything. They arrest you and they can kill you. At the time I wasn’t involved in politics. My father and grandfather were part of the OLF party. The Ethiopian police came to question me, asking who was supporting the party. In 2013/14 they arrested me and held me for two months in the prison of Diradawa. They wanted to know where my uncle was. They didn’t give me food, only bread and water once every three days, and we had to do a lot of work in the prison.” (

“I left Ethiopia because of the political situation. I’m Oromo and in 1991 there was conflict between Tigrinya and Oromo. My grandfather and my father fought for the Oromo. Later, my father was arrested and my brother shot dead at university by the government. In Ethiopia if you are Oromo you can’t do anything. They arrest you and they can kill you. At the time I wasn’t involved in politics. My father and grandfather were part of the OLF party. The Ethiopian police came to question me, asking who was supporting the party. In 2013/14 they arrested me and held me for two months in the prison of Diradawa. They wanted to know where my uncle was. They didn’t give me food, only bread and water once every three days, and we had to do a lot of work in the prison.” ( “About seven months after Osama’s arrest, security officers stopped Firas at the gate of his university. “If you keep asking about your brothers, we will cut out your tongue,” they told him. That day, Firas fled Syria.” (

“About seven months after Osama’s arrest, security officers stopped Firas at the gate of his university. “If you keep asking about your brothers, we will cut out your tongue,” they told him. That day, Firas fled Syria.” ( “Compounding Italy’s frustration is the fact that its northern neighbours, including France, Switzerland and Austria, have in effect closed their borders to migrants, preventing what had been a natural flow of refugees towards more prosperous parts of Europe.” (

“Compounding Italy’s frustration is the fact that its northern neighbours, including France, Switzerland and Austria, have in effect closed their borders to migrants, preventing what had been a natural flow of refugees towards more prosperous parts of Europe.” ( “A 16 year old, named Djoka, from Sudan reported, “They gave me electricity with a stick, many times… I was too weak, I couldn’t resist… They took both my hands and put them on the machine.” (

“A 16 year old, named Djoka, from Sudan reported, “They gave me electricity with a stick, many times… I was too weak, I couldn’t resist… They took both my hands and put them on the machine.” ( “Anti-immigrant Northern League leader Matteo Salvini said Tuesday there would be “mass expulsions” of migrants when the League gained power, after the most recent revolt in a migrant centre in Italy.” (

“Anti-immigrant Northern League leader Matteo Salvini said Tuesday there would be “mass expulsions” of migrants when the League gained power, after the most recent revolt in a migrant centre in Italy.” ( “An Afghan migrant travelled 400 kilometres (250 miles) along an Italian highway strapped by leather belts to the bottom of a lorry, according to police.” (

“An Afghan migrant travelled 400 kilometres (250 miles) along an Italian highway strapped by leather belts to the bottom of a lorry, according to police.” ( “In an intercepted phone call, Mafia businessman Salvatore Buzzi was heard telling his assistant Pierina Chiaravalle: “Do you have any idea how much I make on these immigrants? Drug trafficking is less profitable.”” (

“In an intercepted phone call, Mafia businessman Salvatore Buzzi was heard telling his assistant Pierina Chiaravalle: “Do you have any idea how much I make on these immigrants? Drug trafficking is less profitable.”” ( A Nigerian man who had recently fled to Europe to escape Boko Haram militants was beaten to death on the streets of Italy this week as he tried to defend his wife against racist abuse. (

A Nigerian man who had recently fled to Europe to escape Boko Haram militants was beaten to death on the streets of Italy this week as he tried to defend his wife against racist abuse. ( “Syria is burning; towns are destroyed and that’s why people are on the move, that’s why we have an avalanche, a tsunami of people on the move towards Europe… As long as there’s no resolution in Syria and no improved conditions in neighbouring countries, people will move.” (

“Syria is burning; towns are destroyed and that’s why people are on the move, that’s why we have an avalanche, a tsunami of people on the move towards Europe… As long as there’s no resolution in Syria and no improved conditions in neighbouring countries, people will move.” ( High ships come in bearing black strangers

High ships come in bearing black strangers No one leaves home unless/ home is the mouth of a shark. You only run for the border / when you see the whole city / running as well. (

No one leaves home unless/ home is the mouth of a shark. You only run for the border / when you see the whole city / running as well. ( “I hate the indifferent. I believe that living means taking sides. Those who really live cannot help being a citizen and a partisan. Indifference and apathy are parasitism, perversion, not life. That is why I hate the indifferent.” Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks

“I hate the indifferent. I believe that living means taking sides. Those who really live cannot help being a citizen and a partisan. Indifference and apathy are parasitism, perversion, not life. That is why I hate the indifferent.” Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks I was tickled to see that someone on Tripadvisor had described the restaurant immediately underneath our flat as being in an ‘absolutely insignificant quarter of the city’. The area may not have a name as such (we have to describe it using a series of awkward coordinates) or any singular identity but it is of significance to us for two reasons: one, there’s the fact that we live here, and two, that it embodies certain tendencies and pressures both global and local*.

I was tickled to see that someone on Tripadvisor had described the restaurant immediately underneath our flat as being in an ‘absolutely insignificant quarter of the city’. The area may not have a name as such (we have to describe it using a series of awkward coordinates) or any singular identity but it is of significance to us for two reasons: one, there’s the fact that we live here, and two, that it embodies certain tendencies and pressures both global and local*.

It’s a bright blue Monday morning in mid-October 2016 and I’m standing at the corner of Via dei Gracchi and Via Alessandro Farnese in the centre of Rome, having just left work. I’m partly waiting to cross the road and partly trying to get fivethirtyeight.com to load on my phone. There’s a guy in a car looking at me, stopped at the traffic lights on this quiet street, shouting and laughing. At first I don’t think he’s talking to me, maybe on his phone or to himself. But no, it’s me, he’s beckoning me over, and he seems to know my name, so I must know him, but I feel bad because I have no idea whatsoever who he is. He looks very Italian, in a slightly

It’s a bright blue Monday morning in mid-October 2016 and I’m standing at the corner of Via dei Gracchi and Via Alessandro Farnese in the centre of Rome, having just left work. I’m partly waiting to cross the road and partly trying to get fivethirtyeight.com to load on my phone. There’s a guy in a car looking at me, stopped at the traffic lights on this quiet street, shouting and laughing. At first I don’t think he’s talking to me, maybe on his phone or to himself. But no, it’s me, he’s beckoning me over, and he seems to know my name, so I must know him, but I feel bad because I have no idea whatsoever who he is. He looks very Italian, in a slightly